This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and is not used for commercial purposes.

© 2022 The Authors. published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd on behalf of Chinese Medical Association.

In a 2012 study, occasional and low cumulative cannabis use was not associated with adverse effects on pulmonary function.1 With tobacco, the more used, the more loss of air flow rate and lung volume. The same was not true with cannabis use. Air flow rate increased rather than decreased with increased exposure to cannabis up to a certain level.

An important factor that helped explain the difference in effects from tobacco and cannabis was the amount of each that was smoked. Tobacco users typically smoked 10-20 cigarettes daily, some even more. Cannabis smokers, on average, smoked only two to three times a month, so the average exposure to cannabis was much lower than for tobacco. People experiment with cannabis in their late teens and 20s, and some consume relatively low levels for years. Although heavy exposure to cannabis might damage the lungs, reliable estimates of the effects of heavy use were not available in the 2012 study, as heavy users were relatively rare in the study population.

In the current analysis, we used data from UK Biobank (UKB) to assess the effect of cannabis on coronavirus disease (COVID-19) infection and to determine whether cannabis lung damage might facilitate COVID-19 infection in formerly heavy users.

The UKB is a large prospective observational study comprising about 500,000 men and women (N = 229,134 men, N = 273,402 women), more than 90% White, aged 40-69 years at enrollment. Participants were recruited from across 22 centers located throughout England, Wales, and Scotland, between 2006 and 2010, and continue to be longitudinally followed for capture of subsequent health events.2 This methodology is like that of the Framingham Heart Study,3 with the exception that the UKB program collects postmortem samples, which Framingham did not.

Our UKB application was approved as UKB project 57,245 (S.L. and P.H.R.).

Doctor-diagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is from UKB data field 22,130. At enrollment, the subject was asked on a touchscreen, "Has a doctor ever told you that you have had any of the conditions below?" COPD was one of the options listed.

The subject was asked, "Have you taken cannabis (marijuana, grass, hash, ganja, blow, draw, skunk, weed, spliff, dope), even if it was a long time ago?" If the answer was "yes," cannabis use was recorded in the UKB data field 20,454, maximum frequency of taking cannabis, question asked: "Considering when you were taking cannabis most regularly, how often did you take it?" Answers were 1 = Less than once a month, 2 = Once a month or more, but not every week, 3 = Once a week or more, but not every day, and 4 = Every day. Subject was then asked (UKB data field 20455) "About how old were you when you last had cannabis?"

All UKB subjects who had cannabis-use data, COVID-19 test data, and COPD data were included in the study.

Electronic linkage between UKB records and National Health Service COVID-19 laboratory test results in England were available from March 16 to April 26, 2020, including the peak of daily COVID-19 laboratory-confirmed cases in the current outbreak. During this period, testing of older groups was largely restricted to hospital inpatients with clinical signs of infection, so test positivity is considered a good marker of severe COVID-19.4

Data processing was performed on Minerva, a Linux mainframe with Centos 7.6, at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. We used the UKB Data Parser (ukbb parser), a python-based package that allows easy interfacing with the large UKB data set.5

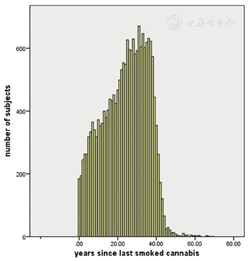

Mean age of subjects was 57 ± 8.1 (mean ± SD). Fifty-four percent were women and 46% were men. Ninety-eight percent were White British. Subjects had not smoked cannabis for 24 ± 11 years (Figure 1).

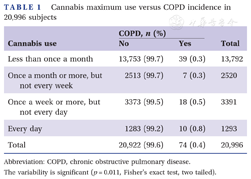

Cannabis maximum use versus COPD incidence in 20,996 subjects is shown in Table 1. Increasing cannabis use was associated with increased COPD prevalence (p = 0.011, Fisher's exact test, two tailed).

Cannabis maximum use versus COPD incidence in 20,996 subjects

Cannabis maximum use versus COPD incidence in 20,996 subjects

| Cannabis use | COPD, n (%) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Less than once a month | 13,753 (99.7) | 39 (0.3) | 13,792 |

| Once a month or more, but not every week | 2513 (99.7) | 7 (0.3) | 2520 |

| Once a week or more, but not every day | 3373 (99.5) | 18 (0.5) | 3391 |

| Every day | 1283 (99.2) | 10 (0.8) | 1293 |

| Total | 20,922 (99.6) | 74 (0.4) | 20,996 |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The variability is significant (p = 0.011, Fisher's exact test, two tailed).

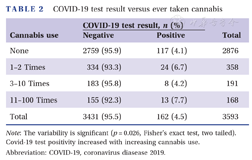

COVID-19 test result versus ever-taking cannabis is shown in Table 2. Increased cannabis use was associated with increased COVID-19 test positivity (p = 0.026, Fisher's exact test, two tailed).

COVID-19 test result versus ever taken cannabis

COVID-19 test result versus ever taken cannabis

| Cannabis use | COVID-19 test result, n (%) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | ||

| None | 2759 (95.9) | 117 (4.1) | 2876 |

| 1-2 Times | 334 (93.3) | 24 (6.7) | 358 |

| 3-10 Times | 183 (95.8) | 8 (4.2) | 191 |

| 11-100 Times | 155 (92.3) | 13 (7.7) | 168 |

| Total | 3431 (95.5) | 162 (4.5) | 3593 |

Note: The variability is significant (p = 0.026, Fisher's exact test, two tailed). Covid-19 test positivity increased with increasing cannabis use.

Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus diasease 2019.

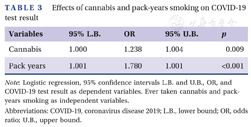

Table 3 shows logistic regression, COVID-19 test result, dependent variable, ever-taking cannabis, pack-years smoking, and independent variables. The effects of cannabis and pack-years smoking on COVID-19 test result were significant and independent.

Effects of cannabis and pack-years smoking on COVID-19 test result

Effects of cannabis and pack-years smoking on COVID-19 test result

| Variables | 95% L.B. | OR | 95% U.B. | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis | 1.000 | 1.238 | 1.004 | 0.009 |

| Pack years | 1.001 | 1.780 | 1.001 | <0.001 |

Note: Logistic regression, 95% confidence intervals L.B. and U.B., OR, and COVID-19 test result as dependent variables. Ever taken cannabis and pack-years smoking as independent variables.

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; L.B., lower bound; OR, odds ratio; U.B., upper bound.

Tobacco smoking increases the risk of lung infections, possibly including COVID-19. Smoking impairs the immune system and almost doubles the risk of tuberculosis. Smoking affects macrophages and cytokine response, and therefore the ability to contain infection. The risk for pneumococcal, legionella, and mycoplasma pneumonia infection is about three to five times higher in smokers.6 In one study, current smokers were more likely to report symptoms, suggesting a diagnosis of COVID-19.7

The effects of smoking cannabis are difficult to assess accurately and to distinguish from the effects of tobacco; nevertheless, cannabis use may cause severe lung damage. Cannabis smoke affects the lungs similarly to tobacco smoke, causing symptoms such as increased cough, sputum, and hyperinflation. Cannabis can produce serious lung diseases with increasing years of use. Cannabis may weaken the immune system, leading to pneumonia. Smoking cannabis has been linked to symptoms of chronic bronchitis. Heavy use of cannabis can result in airway obstruction8 and worse COVID-19 outcome.9 Yet, cannabis use might reduce lung inflammation and inhibit viral replication10 in Covid-19 infections, leading to a better outcome in some cases.11,12

As noted above, we found that the effects of cannabis and pack-years smoking on COVID-19 test result were significant and independent (Table 3). This suggests that the damaging effects of cannabis and smoking on the lung are additive, even though cannabis had not been smoked for a decade or more.

Our study has weaknesses. COVID-19-positive test results were related to cannabis use (Table 2). However, we did not have data relating the frequency of cannabis use to susceptibility COVID-19. In the logistic regression (Table 3), more independent variables would be worthwhile. Moreover, the high incidence of Caucasian subjects might influence the results.

It is never too late to quit smoking tobacco. As soon as a tobacco smoker quits, his chances are diminished of getting cancer and other diseases.13 Our findings imply that cannabis may be similar. Fifteen years after quitting tobacco, risk of coronary heart disease is close to that of a nonsmoker.14 Unlike the heart, the lung does not forget the insult from inhaled tobacco or cannabis, even many years later, but after quitting the lung damage may not further increase.

Changes in cannabis policies across states legalizing it for medical and recreational use suggest that cannabis is winning increased acceptance in our society. Thus, people must understand what is known about the adverse health effects of cannabis.15 As cannabis use becomes more widespread, no doubt more adverse effects will come to light.

This study was supported in part through the computational resources and staff expertise provided by Scientific Computing at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. This study was supported by the Office of Research Infrastructure of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers S10OD018522 and S10OD026880. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data available after approved application to UK Biobank https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/.

UK Biobank has approval from the Northwest Multi-center Research Ethics Committee (MREC), which covers the United Kingdom. It also sought the approval in England and Wales from the Patient Information Advisory Group (PIAG) for gaining access to information that would allow it to invite people to participate. PIAG has since been replaced by the National Information Governance Board for Health & Social Care (NIGB). In Scotland, UK Biobank has approval from the Community Health Index Advisory Group (CHIAG).