There is still uncertainty regarding whether diabetes mellitus (DM) can adversely affect patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy (CEA) for carotid stenosis. The aim of the study was to assess the adverse impact of DM on patients with carotid stenosis treated by CEA.

Eligible studies published between 1 January 2000 and 30 March 2023 were selected from the PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, CENTRAL, and ClinicalTrials databases. The short-term and long-term outcomes of major adverse events (MAEs), death, stroke, the composite outcomes of death/stroke, and myocardial infarction (MI) were collected to calculate the pooled effect sizes (ESs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and prevalence of adverse outcomes. Subgroup analysis by asymptomatic/symptomatic carotid stenosis and insulin/noninsulin-dependent DM was performed.

A total of 19 studies (n = 122,003) were included. Regarding the short-term outcomes, DM was associated with increased risks of MAEs (ES = 1.52, 95% CI: [1.15-2.01], prevalence = 5.1%), death/stroke (ES = 1.61, 95% CI: [1.13-2.28], prevalence = 2.3%), stroke (ES = 1.55, 95% CI: [1.16-1.55], prevalence = 3.5%), death (ES = 1.70, 95% CI: [1.25-2.31], prevalence =1.2%), and MI (ES = 1.52, 95% CI: [1.15-2.01], prevalence = 1.4%). DM was associated with increased risks of long-term MAEs (ES = 1.24, 95% CI: [1.04-1.49], prevalence = 12.2%). In the subgroup analysis, DM was associated with an increased risk of short-term MAEs, death/stroke, stroke, and MI in asymptomatic patients undergoing CEA and with only short-term MAEs in the symptomatic patients. Both insulin- and noninsulin-dependent DM patients had an increased risk of short-term and long-term MAEs, and insulin-dependent DM was also associated with the short-term risk of death/stroke, death, and MI.

In patients with carotid stenosis treated by CEA, DM is associated with short-term and long-term MAEs. DM may have a greater impact on adverse outcomes in asymptomatic patients after CEA. Insulin-dependent DM may have a more significant impact on post-CEA adverse outcomes than noninsulin-dependent DM. Whether DM management could reduce the risk of adverse outcomes after CEA requires further investigation.

Copyright © 2023 The Chinese Medical Association, produced by Wolters Kluwer, Inc. under the CC-BY-NC-ND license. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives License 4.0 (CCBY-NC-ND), where it is permissible to download and share the work provided it is properly cited. The work cannot be changed in any way or used commercially without permission from the journal.

Carotid artery stenosis is an atherosclerotic disease characterized by chronic narrowing of the carotid artery lumen, which induces abnormal distribution of cerebral blood flow and even total occlusion of the carotid artery. Carotid endarterectomy (CEA) is a surgical revascularization procedure that is recommended in symptomatic or asymptomatic patients with 60-99% stenosis of the carotid artery who have low and moderate risks of surgery.[1] Compared to carotid artery stenting (CAS), CEA is associated with lower procedural risks and more effective long-term stroke prevention.[2]

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular diseases.[3] A meta-analysis included carotid artery stenosis patients after revascularization (consisting of CEA and CAS) and showed that DM was associated with increased risks of perioperative stroke, death, death/stroke, and long-term mortality but not perioperative myocardial infarction (MI).[4] However, another recent meta-analysis reported that DM failed to predict adverse outcomes in patients after CAS.[5] The inconsistency of the synthetic results indicated that DM may have a different impact on the outcomes of patients with carotid stenosis treated by CEA, and few conclusive studies with pooled analysis in this regard have been reported. We thus designed and conducted this study to elucidate the impact of DM on the short-term and long-term adverse outcomes of carotid artery stenosis patients after CEA as well as the rates of adverse outcomes after CEA. Only patients with CEA performed after the year 2000 were included for analysis.

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.[6,7] The literature search was conducted by Li FS and Zhang R using the PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, CENTRAL, and ClinicalTrials databases. To ensure both the efficiency of the search and the completeness of the intended studies, we limited the publication date to the period from 1 January 2000 to 30 March 2023, and studies that might comprise CEA cases before 2000 were excluded later. The key terms for the search strategy included 'diabetes Mellitus’, 'T1DM’, 'T2DM’, 'hyperglycemia’, 'hyperglycemic’, 'carotid endarterectomy’, and 'carotid artery stenosis’. The detailed search strategies are presented in Supplementary Tables 1-5, http://links.lww.com/CM9/B591.The authors conducted a manual search of the reference lists of the identified articles to find any additional relevant articles.

The primary outcomes of this meta-analysis were short-term (30-day) and long-term (≥ 3 years) major adverse events (MAEs). MAEs were defined as a combined risk of death, stroke, and MI. Secondary outcomes included the risk of perioperative and long-term outcomes of death, stroke, death/stroke, and MI. If the study did not report composite outcomes, the number of composite outcomes was obtained by summing the occurrence of separate endpoints. The main inclusion criteria of this study were as follows: (1) clinical studies including the endpoints of MAEs, stroke, mortality, and/or MI of DM and non-DM patients with carotid artery stenosis treated by CEA; (2) studies of CEA performed between January 2000 and March 2023; and (3) publications written in English. The exclusion criteria included studies without intended endpoints for DM and non-DM patients with carotid artery stenosis and studies including CEA procedures performed before 2000.

Two reviewers, Niu S and Li FS, independently extracted data from eligible studies. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer, Di X. The following data were collected from the included studies: the occurrence of events, odds ratios (ORs)/relative risks (RRs)/hazard ratios (HRs) of adverse outcomes for diabetes patients, sample size, clinical features of patients with carotid artery stenosis, and other relevant demographic information. An effect size (ES) is the difference between two means (e.g., treatment minus control) divided by the standard deviation. Effect size represents the relative magnitude of the experimental treatment and shows the size of the experimental effect. We used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) to assess the risk of bias of the included studies.[8] The NOS was designed for nonrandomized studies, with two separate scales used to assess case-control studies and cohort studies. Ni L and Rong ZH independently assessed the included studies according to the NOS instructions. A third reviewer, Di X, independently assessed the article to reach consensus if there were discrepancies.

The adjusted HR and associated 95% confidence interval (CI) in multivariable analysis were primarily collected. If there was no adjusted HR reported in the study, the unadjusted HR, RR, OR, and the associated 95% CI were also collected for pooled analysis. Relevant dichotomous data for DM and non-DM patient outcomes were calculated for the OR and associated 95% CI. The pooled ES estimates were computed by the inverse variance weighting method in Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). A random-effect model was applied in this study. Heterogeneity was determined by the chi-squared test and quantified using I2, and I2 >50% was regarded as indicating significant heterogeneity. The prevalence was calculated by the "meta" (version 4.12-0) and "forrestplot" (version 1.9) packages using the R Studio software (PBC, Boston, MA, USA). The Shapiro-Wilk test and log transformation were employed. We also performed subgroup analysis according to the characteristics of carotid artery stenosis (symptomatic/asymptomatic) and the type of DM (insulin-dependent/noninsulin-dependent). Egger’s test and Begg’s test were used for the assessment of publication bias, provided that there were at least eight studies included in the meta-analysis. We preformed sensitivity analyses after exclusion of Eslami et al’s[13] study, giving that the definition of MAEs included "MI, stroke, death as well as discharge to a place other than home". A two-sided P value of less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

A total of 624 records were identified from 5 databases and 19 studies were included for final quantitative synthesis [Figure 1].[9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]

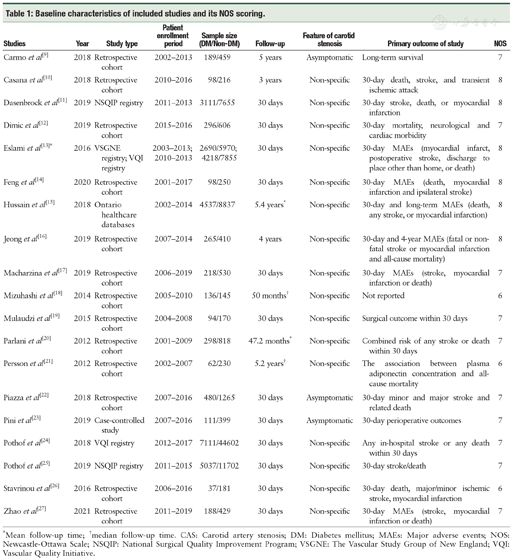

Among the 19 studies in this meta-analysis, 122,003 patients undergoing CEA were included. All CEA procedures were performed after the year 2000, and studies were based on clinical registries, public medical databases, or single-center databases. Of note, patient records in the studies of both Dasenbrock et al[11] and Pothof et al[24] were extracted from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program registry but had different clinical outcomes reported. Eslami et al[13] included patient data from the Vascular Study Group of New England registry in a derivation group and the Vascular Quality Initiative database in a validation group. Seven studies reported long-term results, and three studies only enrolled patients with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Details of the studies’ characteristics and the quality assessment results by the NOS are presented in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included studies and its NOS scoring.

Baseline characteristics of included studies and its NOS scoring.

| Studies | Year | Study type | Patient enrollment period | Sample size (DM/Non-DM) | Follow-up | Feature of carotid stenosis | Primary outcome of study | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carmo et al[9] | 2018 | Retrospective cohort | 2002-2013 | 189/459 | 5 years | Asymptomatic | Long-term survival | 7 |

| Casana et al[10] | 2018 | Retrospective cohort | 2010-2016 | 98/216 | 3 years | Non-specific | 30-day death, stroke, and transient ischemic attack | 8 |

| Dasenbrock et al[11] | 2019 | NSQIP registry | 2011-2013 | 3111/7655 | 30 days | Non-specific | 30-day stroke, death, or myocardial infarction | 8 |

| Dimic et al[12] | 2019 | Retrospective cohort | 2015-2016 | 296/606 | 30 days | Non-specific | 30-day mortality, neurological and cardiac morbidity | 7 |

| Eslami et al[13]* | 2016 | VSGNE registry; VQI registry | 2003-2013; 2010-2013 | 2690/5970; 4218/7855 | 30 days | Non-specific | 30-day MAEs (myocardial infarct, postoperative stroke, discharge to place other than home, or death) | 8 |

| Feng et al[14] | 2020 | Retrospective cohort | 2001-2017 | 98/250 | 30 days | Non-specific | 30-day MAEs (death, myocardial infarction and ipsilateral stroke) | 8 |

| Hussain et al[15] | 2018 | Ontario healthcare databases | 2002-2014 | 4537/8837 | 5.4 years* | Non-specific | 30-day and long-term MAEs (death, any stroke, or myocardial infarction) | 8 |

| Jeong et al[16] | 2019 | Retrospective cohort | 2007-2014 | 265/410 | 4 years | Non-specific | 30-day and 4-year MAEs (fatal or non-fatal stroke or myocardial infarction and all-cause mortality) | 8 |

| Macharzina et al[17] | 2019 | Retrospective cohort | 2006-2019 | 218/530 | 30 days | Non-specific | 30-day MAEs (stroke, myocardial infarction or death) | 7 |

| Mizuhashi et al[18] | 2014 | Retrospective cohort | 2005-2010 | 136/145 | 50 months† | Non-specific | Not reported | 6 |

| Mulaudzi et al[19] | 2015 | Retrospective cohort | 2004-2008 | 94/170 | 30 days | Non-specific | Surgical outcome within 30 days | 7 |

| Parlani et al[20] | 2012 | Retrospective cohort | 2001-2009 | 298/818 | 47.2 months* | Non-specific | Combined risk of any stroke or death within 30 days | 7 |

| Persson et al[21] | 2012 | Retrospective cohort | 2002-2007 | 62/230 | 5.2 years† | Non-specific | The association between plasma adiponectin concentration and all-cause mortality | 6 |

| Piazza et al[22] | 2018 | Retrospective cohort | 2007-2016 | 480/1265 | 30 days | Asymptomatic | 30-day minor and major stroke and related death | 7 |

| Pini et al[23] | 2019 | Case-controlled study | 2007-2016 | 111/399 | 30 days | Asymptomatic | 30-day perioperative outcomes | 7 |

| Pothof et al[24] | 2018 | VQI registry | 2012-2017 | 7111/44602 | 30 days | Non-specific | Any in-hospital stroke or any death within 30 days | 7 |

| Pothof et al[25] | 2019 | NSQIP registry | 2011-2015 | 5037/11702 | 30 days | Non-specific | 30-day stroke/death | 7 |

| Stavrinou et al[26] | 2016 | Retrospective cohort | 2006-2016 | 37/181 | 30 days | Non-specific | 30-day death, major/minor ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction | 6 |

| Zhao et al[27] | 2021 | Retrospective cohort | 2011-2019 | 188/429 | 30 days | Non-specific | 30-day MAEs (stroke, myocardial infarction or death) | 7 |

*Mean follow-up time; †median follow-up time. CAS: Carotid artery stenosis; DM: Diabetes mellitus; MAEs: Major adverse events; NOS: Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; NSQIP: National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; VSGNE: The Vascular Study Group of New England; VQI: Vascular Quality Initiative.

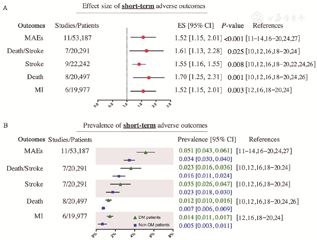

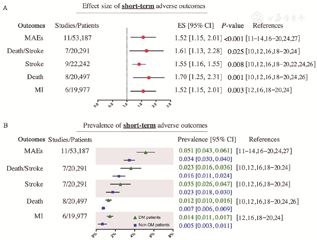

For 30-day MAEs (11 studies, 53,187 patients),[11,12,13,14,16,17,18,19,20,24,27] carotid artery stenosis patients with DM had a higher risk of 30-day MAEs than patients without DM (ES: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.15-2.01, P<0.001; prevalence in DM vs. non-DM: 5.1% vs. 3.4%). And the estimate of the risk of short-term MAEs was not substantially changed in the sensitivity analysis (ES: 1.54, 95% CI: 1.25-1.89; P <0.001). Similarly, the risks of 30-day death/stroke (ES: 1.61, 95% CI: 1.13-2.28, P = 0.025; prevalence in DM vs. non-DM: 2.3% vs. 1.6%),[10,12,16,18,19,20,24] 30-day MI (ES: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.15-2.01, P = 0.003; prevalence in DM vs. non-DM: 1.4% vs. 0.5%),[12,16,18,19,20,24] 30-day mortality (ES: 1.70, 95% CI: 1.25-2.31, P = 0.001; prevalence in DM vs. non-DM: 1.2% vs. 0.7%)[10,12,16,18,19,20,24,26] and 30-day stroke (ES: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.16-1.55, P = 0.008; prevalence in DM vs. non-DM: 3.5% vs. 2.3%) [10,12,16,18,19,20,22,24,26] were all increased in carotid artery stenosis patients with DM after CEA compared with patients without DM [Figure 2]. And the heterogeneity analysis showed that the I2 values for all research indicators are less than 50%. Only the endpoints of short-term MAEs, death, and stroke met the criteria for publication bias assessment, and no significant publication bias was observed according to Begg’s test and Egger’s test [Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 6, http://links.lww. com/CM9/B591].

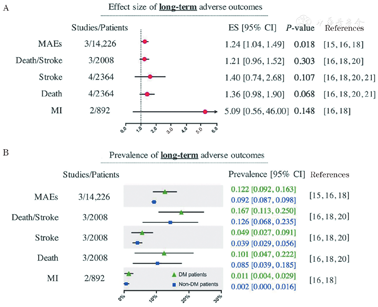

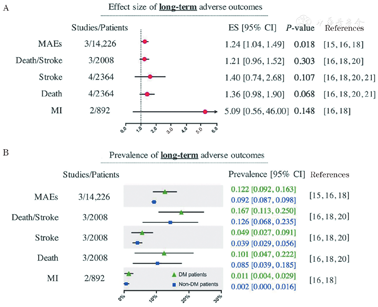

Compared to non-DM patients, DM patients had an increased risk of long-term MAEs after CEA (3 studies, 14,226 patients; ES: 1.24, 95% CI: 1.04-1.49, P = 0.018; prevalence in DM vs. non-DM:12.2% vs. 9.2%).[15,16,18] There was no significant association between DM and a higher long-term risk of stroke,[16,18,20,21] death/stroke,[16,18,20] death,[16,18,20,21] or MI16,18 [Figure 3]. And the heterogeneity analysis shows that the I2 values for all research indicators are less than 50%. Publication bias for long-term outcomes was not assessed due to the limited number of included studies.

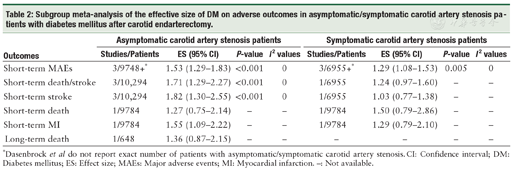

DM predicted increased short-term MAEs in patients with either asymptomatic (ES: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.29-1.83, P <0.001) or symptomatic (ES: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.08-1.53, P = 0.005) carotid artery stenosis.[11,24] In the asymptomatic patient group, DM was associated with an increased risk of short-term stroke,[23,24] death/stroke,[23,24] and MI, [24] although the risk of MI was reported by only one study. Only Pothof et al[24] reported the short-term results of stroke, death/stroke, death, and MI in symptomatic carotid artery stenosis patients, and the results indicated that DM was not associated with an increased risk of death (ES: 1.50, 95% CI: 0.79-2.86). One study reported long-term mortality in asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis patients, and the association between DM and long-term mortality in these patients was insignificant (ES: 1.36, 95% CI: 0.87-2.15).[9] No other long-term outcome was available for the subgroup analysis of asymptomatic/symptomatic DM patients after CEA [Table 2].

Subgroup meta-analysis of the effective size of DM on adverse outcomes in asymptomatic/symptomatic carotid artery stenosis patients with diabetes mellitus after carotid endarterectomy.

Subgroup meta-analysis of the effective size of DM on adverse outcomes in asymptomatic/symptomatic carotid artery stenosis patients with diabetes mellitus after carotid endarterectomy.

| Outcomes | Asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis patients | Symptomatic carotid artery stenosis patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies/Patients | ES (95% CI) | P-value | I2 values | Studies/Patients | ES (95% CI) | P-value | I2 values | |

| Short-term MAEs | 3/9748+* | 1.53 (1.29-1.83) | <0.001 | 0 | 3/6955+* | 1.29 (1.08-1.53) | 0.005 | 0 |

| Short-term death/stroke | 3/10,294 | 1.71 (1.29-2.27) | <0.001 | 0 | 1/6955 | 1.24 (0.97-1.60) | - | - |

| Short-term stroke | 3/10,294 | 1.82 (1.30-2.55) | <0.001 | 0 | 1/6955 | 1.03 (0.77-1.38) | - | - |

| Short-term death | 1/9784 | 1.27 (0.75-2.14) | - | - | 1/9784 | 1.50 (0.79-2.86) | - | - |

| Short-term MI | 1/9784 | 1.55 (1.09-2.22) | - | - | 1/9784 | 1.29 (0.79-2.10) | - | - |

| Long-term death | 1/648 | 1.36 (0.87-2.15) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

*Dasenbrock et al do not report exact number of patients with asymptomatic/symptomatic carotid artery stenosis. CI: Confidence interval; DM: Diabetes mellitus; ES: Effect size; MAEs: Major adverse events; MI: Myocardial infarction. -: Not available.

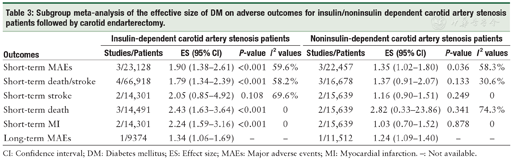

In carotid artery stenosis patients, insulin-dependent DM predicted an increased risk of short-term MAEs,[11,12,24] death/stroke,[12,20,24,25] death,[12,24,26] and MI.[12,24] Patients with noninsulin-dependent DM had an increased risk of short-term MAEs compared with non-DM patients (ES: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.02-1.80, P <0.001),[11,12,24] yet there was no significant association between noninsulin-dependent DM and the short-term outcomes of death/stroke,[12,20,24] stroke,[12,24] death,[12,24,26] or MI.[12,24] Only one study reported that both insulin-dependent and noninsulin-dependent DM were associated with an increased risk of long-term MAEs.[15] No long-term outcomes of stroke, death/stroke, death, or MI were available for the subgroup analysis of noninsulin/insulin-dependent DM patients after CEA [Table 3].

Subgroup meta-analysis of the effective size of DM on adverse outcomes for insulin/noninsulin dependent carotid artery stenosis patients followed by carotid endarterectomy.

Subgroup meta-analysis of the effective size of DM on adverse outcomes for insulin/noninsulin dependent carotid artery stenosis patients followed by carotid endarterectomy.

| Outcomes | Insulin-dependent carotid artery stenosis patients | Noninsulin-dependent carotid artery stenosis patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies/Patients | ES (95% CI) | P-value | I2 values | Studies/Patients | ES (95% CI) | P-value | I2 values | |

| Short-term MAEs | 3/23,128 | 1.90 (1.38-2.61) | <0.001 | 59.6% | 3/22,457 | 1.35 (1.02-1.80) | 0.036 | 58.3% |

| Short-term death/stroke | 4/66,918 | 1.79 (1.34-2.39) | <0.001 | 58.2% | 3/16,678 | 1.37 (0.91-2.07) | 0.133 | 30.6% |

| Short-term stroke | 2/14,301 | 2.05 (0.85-4.92) | 0.108 | 69.6% | 2/15,639 | 1.16 (0.90-1.51) | 0.249 | 0 |

| Short-term death | 3/14,491 | 2.43 (1.63-3.64) | <0.001 | 0 | 2/15,639 | 2.82 (0.33-23.86) | 0.341 | 74.3% |

| Short-term MI | 2/14,301 | 2.24 (1.59-3.16) | <0.001 | 0 | 2/15,639 | 1.03 (0.70-1.52) | 0.878 | 0 |

| Long-term MAEs | 1/9374 | 1.34 (1.06-1.69) | - | - | 1/11,512 | 1.24 (1.09-1.40) | - | - |

CI: Confidence interval; DM: Diabetes mellitus; ES: Effect size; MAEs: Major adverse events; MI: Myocardial infarction. -: Not available.

The current meta-analysis found that DM predicted was associated with increased short-term and long-term risks of adverse outcomes in patients undergoing CEA. Moreover, approximately 5.1% and 12.2% of the DM patients suffered from MAEs after CEA in the short-term and long-term follow-up, respectively (compared to non-DM patients: 3.4% and 9.2%, respectively). Previous studies revealed the impact of DM on the adverse outcomes of carotid revascularization, yet the results were likely to cover the potential bias induced by differences in patient selection and intervention between CAS and CEA procedures.[4,5] The current study found that DM predicted increased short-term and long-term MAEs in patients with carotid stenosis undergoing CEA. To our knowledge, this is the most updated and complete systematic review in this regard.

Moreover, this study showed that patients with DM had an increased short-term risk of death/stroke, death, stroke, and MI. However, studies reporting the long-term results of these endpoints were scarce and this study excluded patients with CEA performed before 2000. In an observational study with a 15.2-year follow-up, patients with carotid stenosis had a 4.4-fold higher risk of MI than the population controls, and DM is also associated with the long-term risk of MI and death in this cohort.[28] Conversely, Mazzaccaro et al[29] suggested that DM was not related to the risk of death (HR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.59-1.22) or stroke (HR: 1.15, 95% CI: 0.79-1.09) during long-term follow-up. In Boulanger et al's[30] study, DM was associated with an increased short-term risk of death (RR: 1.85, 95% CI: 1.56-2.18) but not MI (RR: 1.66, 95% CI: 0.94-2.95). It is possible that other factors, such as a history of coronary comorbidities[31] and plaque characteristics,[32] may affect the predictive value of DM in predicting the outcomes of death/stroke, death, stroke, and MI, but this speculation requires future investigation.

Notably, advancements and shifts in the treatment of carotid stenosis over time also impact the outcomes after CEA. There has been a noticeable improvement in medical treatment for carotid stenosis, including the use of statins, in the last 20 years.[33] Additionally, the CEA procedure is more likely to be centralized in high-volume vascular centers with experienced surgeons.[34] Moreover, due to the development of CAS, CAS could be an alternative for some patients who are considered high risk for undergoing CEA. These factors may explain the decrease in the risk following CEA in the last 20 years. As revealed by Lokuge et al's[35] study, the short-term risks of death/stroke were significantly lower in studies completing recruitment after 2005. The current study was conducted by analyzing the records of patients with CEA performed after the year 2000, which could reduce the potential bias from dated cases.

However, the findings from the current study cannot be directly translated into causal relationships between DM and adverse outcomes after CEA. Nevertheless, studies have revealed that compared with non-DM patients, patients with abnormal glucose homeostasis and insulin resistance have an increased risk of plaque ulceration and rupture.[36] DM-associated plaque instability and plaque atherogenesis could be attributed to the overexpression of inflammatory molecules both in plaque and the peripheral circulation.[37] And, Long et al[38] suggested that poor glycemic control is associated with postoperative morbidity and mortality in patients treated by vascular surgery, including CEA. Notably, in this study, DM was simply a prior-procedure diagnosis, and a patient’s glycemic status could be altered during long-term follow-up. Nevertheless, it is believed that DM patients undergoing CEA would benefit from glycemic surveillance and control. Bath et al[39] indicated a positive association between poor glycemic control (postoperative blood glucose level >180 mg/dL) and an increased risk of adverse outcomes after carotid revascularization (mainly CEA). Although standard diabetes care for DM patients is suggested before and after vascular surgery, further studies are required for the detailed optimization of DM in the setting of CEA treatment.[40]

In the subgroup analysis, we assessed the effect of DM on both asymptomatic and symptomatic carotid artery stenosis treated by CEA. The current study indicated a significant association between DM and short-term MAEs in both asymptomatic and symptomatic subgroups. Notably, the statistically significant results of short-term death/stroke, stroke, and MI were limited to the asymptomatic subgroup, although the number of included studies was relatively small. Indeed, DM is associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness and the presence of calcification and lipid-rich necrotic cores in carotid plaques in both asymptomatic and symptomatic patients.[41,42] Whether DM has stronger association with short-term adverse outcomes after CEA among patients with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis than symptomatic patients is uncertain. For long-term outcomes, the results of long-term MAEs were lacking, and only one study reported insignificant findings between DM and the long-term mortality of asymptomatic patients after CEA.[9] Conversely, Ballotta et al[43] reported reduced long-term survival in patients treated with CEA. The inconsistency among the results could not be resolved in this study.

Additionally, the present study found that both insulin- and noninsulin-dependent DM were associated with an increased risk of short-term and long-term MAEs after CEA. Despite the limited sample size, the results suggested that insulin-dependent DM patients may have a higher cardiovascular risk than noninsulin-dependent DM patients undergoing CEA, as insulin-dependent DM was significantly associated with an increased risk of short-term death/stroke, death, and MI. Conversely, an early study found that insulin-dependent DM did not affect the outcomes of long-term stroke after CEA.[44] Moreover, in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis undergoing CEA, neither insulin-dependent nor noninsulin-dependent DM were linked to an increased risk of long-term mortality.[45] Whether the use of insulin impacts cardiovascular risk is unjustified, and controversies remain.[46,47] On the one hand, insulin is more likely to be applied in patients with more advanced DM, whose cardiovascular risk is notably higher. On the other hand, exogenous insulin may lead to abnormal hypoglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, which are associated with adverse outcomes.[46] Some subgroup analyses of short-term MAEs, short-term death/stroke, and short-term stroke in insulin/noninsulin-dependent patients showed heterogeneity (I2 >50%) among studies. Heterogeneity among the studies may affect the conclusion of the final meta-analysis. Hence, the relationship between insulin therapy and the prognosis of carotid stenosis after CEA remains unclear.

This study has potential clinical implications. First, the present study demonstrated the relationship between DM and adverse outcomes after CEA. Thus, DM patients who need CEA treatment should be aware of the potential higher risk of short-term and long-term MAEs, and clinicians need to discern the risks of MAEs in these patients during hospitalization and follow-up. Second, the results from the subgroup analysis revealed the complexity in the relationship between DM and CEA outcomes. We speculate that patients with insulin-dependent DM may be more prone to short-term adverse outcomes than patients without DM, and the proportion of short-term MAEs may be more attributed to DM in asymptomatic carotid stenosis patients than in symptomatic patients. Third, despite the lack of direct evidence in this study, we are convinced that continued glycemic surveillance and control are beneficial for DM patients undergoing CEA, but the protective effect should be further evaluated in future studies.

There are several limitations of this study. First, most of the included studies were retrospective in nature, and potential bias limits the conclusion. Moreover, in the subgroup meta-analysis of the association of adverse outcomes with asymptomatic/symptomatic or insulin/noninsulin-dependent DM patients with carotid artery stenosis, only one study illustrated short-term mortality, short-term MI, long-term mortality, and long-term MAEs, which may bias the results. Second, the status of DM, including the use of insulin, was diagnosed prior to CEA, which was variable during long-term follow-up. Additionally, other DM variables, such as hemoglobin A1c, were unavailable for the synthetic analysis. Third, for the included studies, there was potential heterogeneity in terms of the study type, endpoint definitions, study design, and sample size. In Eslami et al's[13] study, the definition of MAEs included "MI, stroke, death as well as discharge to a place other than home". However, the estimate of the risk of short-term MAEs was not substantially affected in the sensitivity test (ES 1.54, 95% CI 1.25-1.89; P <0.001). There was also a lack of studies that contained long-term endpoints, which may limit the reliability of the long-term results. We thus used random-effects models, and there was no or little heterogeneity in the analyses of effect size. Last, the studies included in this meta-analysis were observational, which prevents conclusions about causality between DM and MAEs risk. Caution should be taken when interpreting these results, and the optimal treatment should be applied according to individual patients.

In conclusion, in patients with carotid stenosis treated by CEA, DM is associated with an increased short-term risk of MAEs, death/stroke, stroke, death, MI, and long-term risk of MAEs. Insulin-dependent DM may have a higher risk for MAEs after CEA than patients without DM, and DM may have a different role in patients with asymptomatic and symptomatic carotid stenosis. Whether DM treatment reduces the risk of MAEs in patients undergoing CEA requires further validation by large studies.

We thank the public laboratory platform and cell laboratory of National Science and Technology Key Infrastructure on Translational Medicine in Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

None.

Li FS, Zhang R, Di X, Niu S, Rong ZH, Liu CW, Ni L. Diabetes mellitus and adverse outcomes after carotid endarterectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chin Med J 2023; 136: 1401-1409. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002730