版权归中华医学会所有。

未经授权,不得转载、摘编本刊文章,不得使用本刊的版式设计。

除非特别声明,本刊刊出的所有文章不代表中华医学会和本刊编委会的观点。

自2012年11月在上海召开的全国慢性胃炎研讨会制定了《中国慢性胃炎共识意见(2012年,上海)》[1]以来,国际上出台了《H.pylori胃炎京都全球共识意见》[2],既强调了H.pylori的作用,又更加重视慢性胃炎的"可操作的与胃癌风险联系的胃炎评估(operative link for gastritis assessment,OLGA)" [3,4]、甚至"可操作的与胃癌风险联系的肠化生评估(operative link on gastric intestinal metaplasia assessment,OLGIM)"分级分期系统,以及ABC分级标准、Maastricht-5共识[5]和我国第5次全国H.pylori感染处理共识意见[6],慢性胃炎与胃癌的关系与根除H.pylori的作用、慢性胃炎内镜和病理诊断手段的进步等均要求更新共识意见。为此,由中华医学会消化病学分会主办、上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院消化内科暨上海市消化疾病研究所承办的2017年全国慢性胃炎诊治共识会议于2017年7月1日在上海召开。

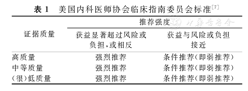

本共识意见包含48项陈述(条款),由中华医学会消化病学分会的部分专家撰写草稿,撰写原则按照循证医学PICO(patient or population,intervention,comparison,outcome)原则,会前对共识意见草案进行了反复讨论和修改。会议期间来自全国各地的75名消化病学专家首先听取了撰写小组专家针对每一项陈述的汇报,在充分讨论后采用改良Delphi方法无记名投票形式通过了本共识意见。陈述的证据来源质量和推荐等级标准参照美国内科医师协会临床指南委员会标准(表1)[7]。每一项陈述投票意见为完全同意和(或)基本同意者超过80%则被视为通过;相反,则全体成员再次讨论;若第2次投票仍未达到前述通过所需要求,则当场修改后进行第3次投票,确定接受或者放弃该项陈述。

1.由于多数慢性胃炎患者无任何症状,因此难以获得确切的患病率。估计的慢性胃炎患病率要高于当地人群中H.pylori感染率。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:97.2%。

H.pylori现症感染者几乎均存在慢性活动性胃炎(chronic active gastritis)[2],即H.pylori胃炎,用血清学方法检测(现症感染或既往感染)阳性者绝大多数存在慢性胃炎。除H.pylori感染外,胆汁反流、药物、自身免疫等因素也可引起慢性胃炎。因此,人群中慢性胃炎的患病率高于或略高于H.pylori感染率。目前我国基于内镜诊断的慢性胃炎患病率接近90%[8]。

2.慢性胃炎尤其是慢性萎缩性胃炎的发生与H.pylori感染密切相关。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:82.1%。

《H.pylori胃炎京都全球共识意见》指出,H.pylori胃炎无论有无症状、伴或不伴有消化性溃疡和胃癌,均应该定义为一种感染性疾病[2]。根据病因分类,H.pylori胃炎是一种特殊类型的胃炎。H.pylori感染与地域、人口种族和经济条件有关。H.pylori感染在儿童时期可导致以胃体胃炎为主的慢性胃炎,而在成人则以胃窦胃炎为主[9]。我国慢性胃炎发病率呈上升趋势,而H.pylori感染率呈下降趋势[8,10]。我国H.pylori的感染率已由2000年前的60.5%降至目前的52.2%左右[11]。除了H.pylori感染,自身免疫性胃炎也可导致胃黏膜萎缩,在50~74岁人群中约20%抗壁细胞抗体阳性[12]。

3.慢性胃炎特别是慢性萎缩性胃炎的患病率一般随年龄增加而上升。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:98.7%。

无论慢性萎缩性胃炎还是非萎缩性胃炎,患病率都随年龄的增长而升高[13]。这主要与H.pylori感染率随年龄增长而上升有关,萎缩、肠化生与"年龄老化"也有一定关系。慢性萎缩性胃炎与H.pylori感染有关[14],年龄越大者其发病率越高,但与性别的关系不明显[15]。这也反映了H.pylori感染产生的免疫反应导致胃黏膜损伤所需的演变过程。

4.慢性胃炎人群中,慢性萎缩性胃炎的比例在不同国家和地区之间存在较大差异,一般与胃癌的发病率呈正相关。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:93.2%。

慢性萎缩性胃炎的发生是H.pylori感染、环境因素和遗传因素共同作用的结果。在不同国家或地区的人群中,慢性萎缩性胃炎的患病率大不相同;此差异不但与各地区H.pylori感染率差异有关,而且与感染的H.pylori毒力基因差异、环境因素不同和遗传背景差异有关。胃癌高发区慢性萎缩性胃炎的患病率高于胃癌低发区。H.pylori感染后免疫反应介导慢性胃炎的发生、发展[16]。外周血Runx3甲基化水平可作为判断慢性萎缩性胃炎预后的指标[17]。慢性胃炎患者的胃癌、结直肠肿瘤、胰腺癌患病率均高于正常者[18]。

5.我国慢性萎缩性胃炎的患病率较高,内镜诊断萎缩性胃炎的敏感性较低,需结合病理检查结果。

推荐等级:条件。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:93.2%。

2014年,由中华医学会消化内镜学分会组织开展了一项横断面调查,纳入包括10个城市、30个中心、共计8 892例有上消化道症状且经胃镜检查证实的慢性胃炎患者[19]。结果表明,在各型慢性胃炎中,内镜诊断慢性非萎缩性胃炎最常见(49.4%),其次是慢性非萎缩性胃炎伴糜烂(42.3%),慢性萎缩性胃炎比例为17.7%;病理诊断萎缩占25.8%,肠化生占23.6%,上皮内瘤变占7.3%。以病理诊断为"金标准" ,则内镜诊断萎缩的敏感度仅为42%,特异度为91%。研究表明我国目前慢性萎缩性胃炎的患病率较高,内镜和病理诊断的符合率有待进一步提高。

1.H.pylori感染是慢性胃炎最主要的病因。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:93.2%。

70%~90%的慢性胃炎患者有H.pylori感染,慢性胃炎活动性的存在高度提示H.pylori感染[20,21]。

2.H.pylori胃炎是一种感染性疾病。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:83.8%。

所有H.pylori感染者几乎都存在慢性活动性胃炎,亦即H.pylori胃炎[20,21]。H.pylori感染与慢性活动性胃炎之间的因果关系符合Koch原则[22,23,24]。H.pylori感染可以在人-人之间传播[25]。因此,不管有无症状和(或)并发症,H.pylori胃炎都是一种感染性疾病[2,5]。

3.胆汁反流、长期服用NSAID(包括阿司匹林)等药物和乙醇摄入是慢性胃炎相对常见的病因。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:97.3%。

胆汁、NSAID(包括阿司匹林)等药物和乙醇可以通过不同机制损伤胃黏膜,这些因素是H.pylori阴性胃炎相对常见的病因[26]。

4.自身免疫性胃炎在我国相对少见。

推荐强度:条件。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:86.3%。

自身免疫性胃炎是一种由自身免疫功能异常所致的胃炎。主要表现为以胃体为主的萎缩性胃炎,伴有血和(或)胃液壁细胞抗体和(或)内因子抗体阳性,严重者因维生素B12缺乏而有恶性贫血表现[27]。其确切的诊断标准有待统一。此病在北欧国家报道较多,我国少有报道[28,29,30],其确切患病率尚不清楚。

5.其他感染性、嗜酸性粒细胞性、淋巴细胞性、肉芽肿性胃炎和Ménétrier病相对少见。

推荐强度:条件。证据质量:低。陈述同意率:97.1%。

除H.pylori感染外,同属螺杆菌的海尔曼螺杆菌可单独(<1%)或与H.pylori共同感染引起慢性胃炎[31]。其他感染性胃炎(包括其他细菌、病毒、寄生虫、真菌)更少见。嗜酸性粒细胞性、淋巴细胞性、肉芽肿性胃炎和Ménétrier病相对少见。随着CD在我国发病率的上升,肉芽肿性胃炎的诊断率可能会有所增加。

6.慢性胃炎的分类尚未统一,一般基于其病因、内镜所见、胃黏膜病理变化和胃炎分布范围等相关指标进行分类。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:98.6%。

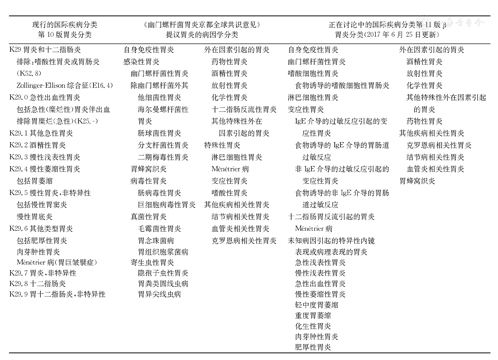

目前,一般基于悉尼系统(Sydney system)[32]和新悉尼系统(updated Sydney system)[26]进行慢性胃炎分类。WHO国际疾病分类(International Classification of Diseases,ICD)第10版(1989年推出)已过时,以病因分类为主的ICD第11版[2]仍在征询意见中(预期2018年推出,部分内容见附录二)。

7.基于病因可将慢性胃炎分成H.pylori胃炎和非H.pylori胃炎两大类。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:83.8%。

病因分类有助于治疗。H.pylori感染是慢性胃炎的主要病因[20,21],将慢性胃炎分成H.pylori胃炎和非H.pylori胃炎有助于慢性胃炎处理中重视对H.pylori检测和治疗。

8.基于内镜和病理诊断可将慢性胃炎分成萎缩性和非萎缩性两大类。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:98.5%。

这是慢性胃炎新悉尼系统的分类方法[26,33]。胃黏膜萎缩可分成单纯性萎缩和化生性萎缩,胃黏膜腺体有肠化生者属于化生性萎缩[34]。

9.基于胃炎分布可将慢性胃炎分为胃窦为主胃炎、胃体为主胃炎和全胃炎三大类。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:85.5%。

这是慢性胃炎悉尼系统的分类方法[32]。胃体为主胃炎尤其是伴有胃黏膜萎缩者,胃酸分泌多减少,发生胃癌的风险增加;胃窦为主者胃酸分泌多增加,发生十二指肠溃疡的风险增加[35,36]。这一胃炎分类法对预测胃炎并发症有一定作用[2,5]。

1.慢性胃炎无特异性临床表现。消化不良症状有无和严重程度与慢性胃炎的分类、内镜下表现、胃黏膜病理组织学分级均无明显相关性。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:100.0%。

在前述(流行病学部分第5条陈述)的一项纳入8 892例慢性胃炎患者全国多中心研究显示,13.1%的患者无任何症状,有症状者常见表现依次为上腹痛(52.9%)、腹胀(48.7%)、餐后饱胀(14.3%)和早饱感(12.7%),近1/3的患者有上述2个以上症状共存,与消化不良症状谱相似[19]。日本一项纳入9 125例慢性胃炎临床研究中,40%的患者有消化不良表现,慢性胃炎与功能性消化不良在临床表现和精神心理状态方面无显著差异[37]。国内Wei等 [38]对符合罗马Ⅲ功能性消化不良诊断的233例患者进行胃镜病理活组织检查(以下简称活检),发现H.pylori胃炎占37.7%,症状以上腹不适综合征(epigastric pain syndrome,EPS)为主,但无大样本研究进一步证实。Carabotti等[39]比较了胃窦局灶性胃炎与全胃炎患者的消化不良症状,结果两者之间无显著差异。Redéen等[40]发现不同内镜表现和病理组织学结果的慢性胃炎患者症状的严重程度与内镜所见和病理组织学分级无明显相关性。

2.自身免疫性胃炎可长时间缺乏典型临床症状,胃体萎缩后首诊症状主要以贫血和维生素B12缺乏引起神经系统症状为主。

推荐强度:条件。证据质量:低。陈述同意率:98.6%。

传统观点认为自身免疫性胃炎好发于老年北欧女性,但最新流行病调查研究显示以壁细胞抗体阳性为诊断标准,该病在人群中的总发病率为2%,老年女性发病率可达4%~5%,且无种族、地域特异性[41]。患者在胃体萎缩前无典型临床表现,进展至胃体萎缩后多以贫血和维生素B12缺乏引起的神经系统症状就诊[28]。有研究表明,因胃体萎缩、胃酸减少引起缺铁性小细胞性贫血可先于大细胞性贫血出现[42]。自身免疫性胃炎恶性贫血合并原发性甲状旁腺亢进与1型糖尿病的发病率较健康人群增高3~5倍[43,44]。一项国外最新的横断面研究纳入379例临床诊断为自身免疫性胃炎的患者,餐后不适综合征(postprandial distress syndrome, PDS)占有消化道症状者的60.2%,独立相关因素为低龄(<55岁)(OR=1.6,95%CI 1.0~2.5)、吸烟(OR=2.2,95%CI 1.2~4.0)、贫血(OR=3.1,95%CI 1.5~6.4)[45],国内尚无自身免疫性胃炎大样本研究。

3.其他感染性、嗜酸性粒细胞性、淋巴细胞性、肉芽肿性胃炎和Ménétrier病症状表现多样。

推荐强度:条件。证据质量:低。陈述同意率:98.6%。

淋巴细胞性胃炎:内镜下表现为绒毛状、疣状胃炎伴糜烂,病理特征为胃黏膜上皮内淋巴细胞>25/100上皮细胞。临床表现多样,1/3至1/2的患者表现为食欲下降、腹胀、恶心、呕吐,1/5的患者合并低蛋白血症与乳糜泻[46]。

肉芽肿性胃炎:CD累及上消化道表现之一,Horjus Talabur Horje等[47]在新诊断的108例CD患者中,发现55%的病例伴有胃黏膜损害,病理表现为局灶性胃炎(focally enhanced gastritis)、肉芽肿性胃炎。

1.慢性胃炎的内镜诊断系指肉眼或特殊成像方法所见的黏膜炎性变化,需与病理检查结果结合做出最终判断。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:94.2%。

慢性萎缩性胃炎的诊断包括内镜诊断和病理诊断,而普通白光内镜下判断的萎缩与病理诊断的符合率较低,确诊应以病理诊断为依据[19,48,49,50,51]。

2.内镜结合病理组织学检查,可诊断慢性胃炎为慢性非萎缩性胃炎和慢性萎缩性胃炎两大基本类型。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:低。陈述同意率:98.5%。

多数慢性胃炎的基础病变均为炎性反应(充血渗出)或萎缩,因此将慢性胃炎分为慢性非萎缩性胃炎和慢性萎缩性胃炎[33],此也有利于与病理诊断的统一。慢性非萎缩性胃炎内镜下可见黏膜红斑、黏膜出血点或斑块、黏膜粗糙伴或不伴水肿、充血渗出等基本表现[33]。慢性萎缩性胃炎在内镜下可见黏膜红白相间,以白相为主,皱襞变平甚至消失,部分黏膜血管显露;可伴有黏膜颗粒或结节状等表现[33]。

慢性胃炎可同时存在糜烂、出血或胆汁反流等征象,这些在内镜检查中可获得可靠的证据。其中糜烂可分为2种类型,即平坦型和隆起型,前者表现为胃黏膜有单个或多个糜烂灶,其大小从针尖样到直径数厘米不等;后者可见单个或多个疣状、膨大皱襞状或丘疹样隆起,直径5~10 mm,顶端可见黏膜缺损或脐样凹陷,中央有糜烂[52]。糜烂的发生可与H.pylori感染和服用黏膜损伤药物等有关[53,54,55]。因此,在诊断时应予以描述,如慢性非萎缩性胃炎或慢性萎缩性胃炎伴糜烂、胆汁反流等[2]。

3.特殊类型胃炎的内镜诊断必须结合病因和病理。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:低。陈述同意率:98.5%。

特殊类型胃炎的分类与病因和病理有关,包括化学性、放射性、淋巴细胞性、肉芽肿性、嗜酸细胞性,以及其他感染性疾病所致者等[33]。

4.放大内镜结合染色对内镜下胃炎病理分类有一定帮助。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:100.0%。

放大内镜结合染色能清楚地显示胃黏膜微小结构,可指导活检部分,对胃炎的诊断和鉴别诊断和早期发现上皮内瘤变和肠化生具有参考价值。目前,亚甲基蓝染色结合放大内镜对肠化生和上皮内瘤变仍保持了较高的准确率[56,57]。苏木精、靛胭脂、醋酸染色对上皮内瘤变也有诊断作用[57,58,59,60]。

5.电子染色放大内镜和共聚焦激光显微内镜对慢性胃炎诊断和鉴别诊断有一定价值。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:98.6%。

电子染色放大内镜对于慢性胃炎和胃癌前病变具有较高的敏感度和特异度[61,62,63,64,65,66],但其具体表现特征和分型尚无完全统一的标准。共聚焦激光显微内镜光学活检技术对胃黏膜的观察可达到细胞水平,能够实时辨认胃小凹、上皮细胞、杯状细胞等细微结构变化,对慢性胃炎的诊断和组织学变化分级(慢性炎性反应、活动性、萎缩和肠化生)具有一定的参考价值[67,68,69]。同时,光学活检可选择性对可疑部位进行靶向活检,有助于提高活检取材的准确性[70,71]。

6.规范的慢性胃炎内镜检查报告,描述内容至少应包括病变部位和特征。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:94.2%。

建议规范慢性胃炎的内镜检查报告,描述内容除了包括胃黏膜病变部位和特征外,建议最好包括病变性质、胃镜活检部位和活检块数、快速尿素酶检查H.pylori结果等。

7.活检病理组织学对慢性胃炎的诊断至关重要,应根据病变情况和需要进行活检。临床诊断时建议取2~3块,分别在胃窦、胃角和胃体部位活检;可疑病灶处另外多取活检[33]。有条件时,活检可在色素或电子染色放大内镜和共聚焦激光显微内镜引导下进行[70,72,73,74]。

推荐等级:条件。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:91.3%。

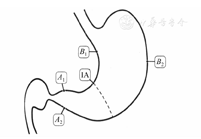

对于慢性胃炎内镜活检块数的多少,历届共识意见研讨会争议较多[1,75,76],不利于规范我国慢性胃炎的内镜活检和病理资料库的积累。建议有条件的单位根据悉尼系统的要求取5块标本(图1)[33],即在胃窦和胃体各取2块,胃角取1块,有利于我国慢性胃炎病理资料库的建立;仅用于临床诊断的可以取2~3块标本。

注:A1和A2为胃窦2块组织取材点,分别取自距幽门2~3 cm处的大弯和小弯;IA为胃角1块组织取材点;B1和B2为胃体2块组织取材点,分别取自距贲门8 cm的大弯(胃体大弯中部)和距胃角近侧4 cm的小弯

1.要重视贲门炎诊断,必要时增加贲门部黏膜活检。

推荐等级:条件。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:84.1%。

贲门炎是慢性胃炎中未受到重视的一种类型,和GERD、Barrett食管等存在一定关系,值得今后加强研究。反流性食管炎如疑合并贲门炎时,宜取活检。

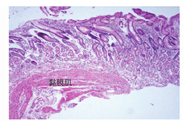

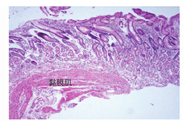

2.标本要足够大,达到黏膜肌层(图2)。不同部位的标本需分开装瓶。内镜医师应向病理科提供取材部位、内镜所见和简要病史等临床资料。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:100.0%。

标本过浅(少)未达黏膜肌层者,失去了判断有无萎缩的依据。活检对诊断自身免疫性胃炎十分重要,诊断时要核实取材部位(送检标本需分瓶装),另外,临床和实验室资料亦很重要,严重的H.pylori感染性胃炎患者,其胃体黏膜也可能有明显的炎性反应或萎缩。内镜医师应向病理科提供取材部位、内镜所见和简要病史等临床资料,加强临床和病理的联系,可以取得更多的反馈信息[1,33,75,76]。

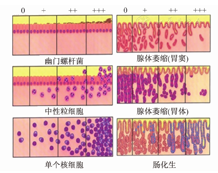

3.慢性胃炎有5种组织学变化要分级,即H.pylori、炎性反应、活动性、萎缩和肠化生,分成无、轻度、中度和重度4级(0、+、++、+++)。分级标准采用我国慢性胃炎的病理诊断标准(附录)和新悉尼系统的直观模拟评分法(visual analogue scale)并用。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:100.0%。

直观模拟评分法是新悉尼系统(1996)为提高慢性胃炎国际间交流一致率而提出的[33]。我国慢性胃炎的病理诊断标准是采用文字描述的[1,75,76],比较具体,容易操作,与新悉尼系统基本类似。将我国文字描述的病理诊断标准与新悉尼系统评分图(图3)结合,可以提高我国慢性胃炎病理诊断与国际诊断标准的一致性。对炎性反应明显而H-E染色切片未发现H.pylori者,要作特殊染色仔细寻找,推荐用较简便的吉姆萨(Giemsa)染色,也可按各病理室惯用的染色方法,有条件的单位可行免疫组织化学检测。胃肠道黏膜是人体免疫系统的主要组成部分,存在生理性免疫细胞(主要为淋巴细胞、组织细胞、树突状细胞、浆细胞),这些细胞形态在常规H-E染色切片上难以与慢性炎性细胞区分。病理医师建议在内镜检查无明显异常情况下,高倍镜下平均每个腺管有1个单个核细胞浸润可不作为"病理性"胃黏膜对待[1,32,33,75,76,77]。

4.慢性胃炎病理诊断应包括部位分布特征和组织学变化程度。有病因可循的要报告病因。胃窦和胃体炎性反应程度相差二级或以上时,加上"为主"修饰词,如"慢性(活动性)胃炎,胃窦为主"。病理检查要报告每块活检标本的组织学变化,推荐使用表格式的慢性胃炎病理报告。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率98.6%。

病理诊断要报告每块活检标本的组织学变化,可向临床医师反馈更详细的信息,有利于减少活检随机误差所造成的结论偏倚,方便临床进行治疗前后比较[33,75]。表格式的慢性胃炎病理报告(图4)可克服活检随机性的缺点,信息简明、全面,便于治疗前后比较。

5.慢性胃炎病理活检显示固有腺体萎缩,即可诊断为萎缩性胃炎,而不必考虑活检标本的萎缩块数和程度。临床医师可根据病理结果并结合内镜表现,最后做出萎缩范围和程度的判断。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:98.6%。

早期或多灶性萎缩性胃炎的胃黏膜萎缩呈灶性分布。即使活检块数少,只要病理活检显示有固有腺体萎缩,即可诊断为萎缩性胃炎。需注意:一切原因引起黏膜损伤的病理过程都可造成腺体数量减少,如于糜烂或溃疡边缘取的活检,不能视为萎缩性胃炎;局限于胃小凹区域的肠化生不算萎缩;黏膜层出现淋巴滤泡不算萎缩,要通过观察其周围区域的腺体情况来决定;此外,活检组织太浅(未达黏膜肌层者)、组织包埋方向不当等因素均可影响对萎缩的判断。

6.肠化生范围和肠化生亚型对预测胃癌发生危险性均有一定的价值,AB-PAS和HID-AB黏液染色能区分肠化生亚型。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:87.0%。

研究强调重视肠化生范围,肠化生范围越广,发生胃癌的危险性越高。新近Meta分析提示肠化生分型对胃癌的预测亦有积极意义,不完全型和(或)结直肠型肠化生与胃癌发生更相关[78,79,80,81]。但从病理检测实际情况看,慢性胃炎的肠化生以混合型肠化生多见,不完全型和(或)结直肠型肠化生的检出与活检数量的多少有密切关系,即存在取样误差问题。AB-PAS染色对不明显肠化生的诊断很有帮助。

7.异型增生(上皮内瘤变)是最重要的胃癌癌前病变。有异型增生(上皮内瘤变)的要注明,分为轻度、中度和重度异型增生(或低级别和高级别上皮内瘤变)。

推荐等级:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:94.2%。

异型增生和上皮内瘤变是同义词,后者是WHO国际癌症研究协会推荐使用的术语[82]。但是,不论国际还是国内,术语的应用和译法意见尚不完全一致,病理组建议可以同时使用这2个术语[83,84]。

1.慢性胃炎的治疗应尽可能针对病因,遵循个体化原则。治疗目的是去除病因、缓解症状和改善胃黏膜炎性反应。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:98.5%。

慢性胃炎的治疗目的是去除病因、缓解症状和改善胃黏膜组织学。慢性胃炎的消化不良症状的处理与功能性消化不良相同。无症状、H.pylori阴性的慢性非萎缩性胃炎无需特殊治疗;但对慢性萎缩性胃炎,特别是严重的慢性萎缩性胃炎或伴有上皮内瘤变者应注意预防其恶变。

2.饮食和生活方式的个体化调整可能是合理的建议。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:低。陈述同意率:97.1%。

虽然尚无明确的证据显示某些饮食摄入与慢性胃炎症状的发生存在因果关系,且亦缺乏饮食干预疗效的大型临床研究,但是饮食习惯的改变和生活方式的调整是慢性胃炎治疗的一部分。目前,临床医师也常建议患者尽量避免长期大量服用引起胃黏膜损伤的药物(如NSAID),改善饮食与生活习惯(如避免过多饮用咖啡、大量饮酒和长期大量吸烟)[85]。

3.证实H.pylori阳性的慢性胃炎,无论有无症状和并发症,均应进行H.pylori根除治疗,除非有抗衡因素存在。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:81.1%。

如前所述,不管有无症状和(或)并发症,H.pylori胃炎均属感染性疾病,应该进行H.pylori根除治疗,除非有抗衡因素存在(抗衡因素包括患者伴存某些疾病、社区高再感染率、卫生资源优先度安排等)。

4.H.pylori胃炎治疗采用我国第5次H.pylori共识推荐的铋剂四联H.pylori根除方案。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:97.1%。

我国第5次H.pylori感染处理共识推荐H.pylori根除方案为铋剂四联方案:PPI+铋剂+2种抗菌药物,疗程为10或14 d[6]。

5.H.pylori根除治疗后所有患者都应常规进行H.pylori复查,评估根除治疗的效果;评估最佳的非侵入性方法是尿素呼气试验(13C/14C);评估应在治疗完成后至少4周进行。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:94.2%。

6.伴胆汁反流的慢性胃炎可应用促动力药和(或)有结合胆酸作用的胃黏膜保护剂。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:100.0%。

胆汁反流也是慢性胃炎的病因之一。幽门括约肌功能不全导致胆汁反流入胃,后者削弱或破坏胃黏膜屏障功能,使胃黏膜遭到消化液作用,产生炎性反应、糜烂、出血和上皮化生等病变。促动力药如盐酸伊托必利、莫沙必利和多潘立酮等可防止或减少胆汁反流。而有结合胆酸作用的铝碳酸镁制剂[86,87],可增强胃黏膜屏障并可结合胆酸,从而减轻或消除胆汁反流所致的胃黏膜损伤。有条件时,可酌情短期应用熊去氧胆酸制剂[88,89]。

7.服用引起胃黏膜损伤的药物如NSAID(包括阿司匹林)后出现慢性胃炎症状者,建议加强抑酸和胃黏膜保护治疗;根据原发病充分评估,必要时停用损害胃黏膜的药物。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:95.6%。

临床上常见的能引起胃黏膜损伤的药物主要有抗血小板药物、NSAID(包括阿司匹林)等。当出现药物相关胃黏膜损伤时,首先根据患者使用药物的治疗目的评估患者是否可以停用该药物;对于须长期服用以上药物者,应进行H.pylori筛查并根除,并根据病情或症状严重程度选用PPI、H2受体拮抗剂(histamine-receptor antagonists,H2RA)或胃黏膜保护剂。多项病例对照研究和随机对照试验研究显示,PPI是预防和治疗NSAID相关消化道损伤的首选药物,优于H2RA和黏膜保护剂[90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99]。

8.有胃黏膜糜烂和(或)以上腹痛和上腹烧灼感等症状为主者,可根据病情或症状严重程度选用胃黏膜保护剂、抗酸剂、H2RA或PPI。推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:高。

以上腹饱胀、恶心或呕吐等为主要症状者可用促动力药。推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:高。

具有明显的进食相关的腹胀、纳差等消化功能低下症状者,可考虑应用消化酶制剂。推荐强度:条件。证据质量:低。

陈述同意率:98.6%。

胃酸/胃蛋白酶在胃黏膜糜烂(尤其是平坦糜烂)和以上腹痛或上腹烧灼感等症状的发生中起重要作用,抗酸或抑酸治疗对愈合糜烂和消除上述症状有效[100]。胃黏膜保护剂如吉法酯、替普瑞酮、铝碳酸镁制剂、瑞巴派特、硫糖铝、依卡倍特、聚普瑞锌等可改善胃黏膜屏障,促进胃黏膜糜烂愈合[101,102,103],但对症状的改善作用尚有争议。抗酸剂起效迅速但作用相对短暂;包括奥美拉唑、艾司奥美拉唑、雷贝拉唑、兰索拉唑、泮托拉唑和艾普拉唑等在内的PPI抑酸作用强而持久,可根据病情或症状严重程度选用[104,105,106,107,108]。PPI主要在肝脏经细胞色素P450系统中的CYP2C19、CYP3A4代谢,可能与其他药物发生相互作用。其中奥美拉唑发生率最高,艾司奥美拉唑是奥美拉唑的纯左旋结构,既保证了强而持久的抑酸作用,又明显降低了对CYP2C19的依赖。泮托拉唑和艾普拉唑与CYP2C19亲和力低[109],雷贝拉唑主要经非酶代谢途径;它们均较少受CYP2C19酶基因多态性的影响。在慢性胃炎的治疗中,建议PPI应用需遵从个体化原则,对于长期应用者要掌握适应证、有效性和患者的依从性,并全面评估获益和风险[110]。而H2RA,根据2006年Cochrane数据库系统综述所示,对于非溃疡性消化不良症状,H2RA的疗效较安慰剂高22%;PPI的疗效较安慰剂高14%,从而认为两者治疗消化不良症状的疗效相当[111]。在一项多中心前瞻性单臂开放标签研究中,纳入10 311例临床诊断为慢性胃炎且有症状的患者,给予法莫替丁20 mg/d共4周,结果发现法莫替丁可明显缓解患者上腹痛、上腹饱胀和胃灼热的症状[112]。另外有研究通过对十二指肠球部溃疡患者的比较,发现亚洲患者的壁细胞总量和酸分泌能力明显低于高加索人[113]。因此,某些患者选择抗酸剂或H2RA适度抑酸治疗可能更经济且不良反应更少[114]。

上腹饱胀或恶心、呕吐的发生可能与胃排空迟缓相关,胃动力异常是慢性胃炎不可忽视的因素。促动力药可改善上述症状[115]。多潘立酮是选择性外周多巴胺D2受体拮抗剂,能增加胃和十二指肠动力,促进胃排空[116]。需要注意的是,因有报道在多潘立酮日剂量超过30 mg和(或)伴有心脏病患者、接受化学疗法的肿瘤患者、电解质紊乱等严重器质性疾病的患者、年龄>60岁的患者中,发生严重室性心律失常甚至心源性猝死的风险可能升高[117],因此,2016年9月国家食品药品监督管理总局就多潘立酮说明书有关药物安全性方面进行了修订,建议上述患者应用时要慎重,或在医师指导下使用。莫沙必利是选择性5-羟色胺4受体激动剂,能促进食管动力、胃排空和小肠传输,莫沙必利的应用经验主要是在包括我国在内的多个亚洲国家[118],临床上治疗剂量未见心律失常活性,对QT间期亦无临床有意义的影响。伊托必利为多巴胺D2受体拮抗剂和乙酰胆碱酯酶抑制剂,前瞻性、多中心、随机对照双盲研究显示盐酸伊托必利可显著改善消化不良症状[119,120]。由此2016年"罗马Ⅳ功能性胃肠病"指出,盐酸伊托必利可有效缓解腹胀、早饱等症状,且不良反应发生率低[121]。

另外,可针对进食相关的中上腹饱胀、纳差等消化不良症状应用消化酶制剂,推荐患者餐中服用,效果优于餐前和餐后服用,目的在于在进食同时提供充足的消化酶,以帮助营养物质的消化,缓解相应症状。消化酶制剂种类较多,我国常用的包括米曲菌胰酶片、复方阿嗪米特肠溶片、胰酶肠溶胶囊、复方消化酶胶囊等。

9.有消化不良症状且伴明显精神心理因素的慢性胃炎患者可用抗抑郁药或抗焦虑药。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:94.2%。

流行病学调查发现,精神心理因素与消化不良症状发生相关,尤其是焦虑症和抑郁症[122]。抗抑郁药物或抗焦虑药物可作为伴有明显精神心理因素者,以及常规治疗无效和疗效差者的补救治疗[123,124],包括三环类抗抑郁药或选择性5-羟色胺再摄取抑制剂等。上述治疗主要是针对消化不良症状。

10.中医、中药可用于慢性胃炎的治疗。

推荐强度:条件。证据质量:低。陈述同意率:89.8%。

多个中成药可缓解慢性胃炎的消化不良症状,甚至可能有助于改善胃黏膜病理状况;如摩罗丹[125]、胃复春、羔羊胃B12胶囊等。但目前尚缺乏多中心、安慰剂对照、大样本、长期随访的临床研究证据。

1.慢性胃炎特别是慢性萎缩性胃炎的进展与演变受多种因素影响,伴有上皮内瘤变者发生胃癌的危险性有不同程度的增加。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:98.6%。

当然,反复或持续H.pylori感染、不良饮食习惯等均为加重胃黏膜萎缩和肠化生的潜在因素[126]。水土中含过多硝酸盐,微量元素比例失调,吸烟,长期饮酒,缺乏新鲜蔬菜与水果和所含的必要营养素,经常食用霉变、腌制、熏烤和油炸等快餐食物,过多摄入食盐,有胃癌家族史,均可增加慢性萎缩性胃炎患病风险或加重慢性萎缩性胃炎甚至增加癌变可能[127,128]。新近报告称,AMPH、PCDH10、RSPO2、SORCS3和ZNF610的甲基化可预示胃黏膜病变的进展[129]。

慢性萎缩性胃炎常合并肠化生,少数出现上皮内瘤变,经历长期的演变,少数病例可发展为胃癌[130,131,132]。低级别上皮内瘤变大部分可逆转而较少恶变为胃癌[126,133,134]。

2.除遗传因素、H.pylori感染情况和饮食状况、生活习惯因素以外,年龄与组织学的萎缩甚至肠化生的出现相关。综合多种因素可以"胃龄"反映胃黏膜细胞的衰老状况。

推荐强度:条件。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:84.0%。

多数慢性非萎缩性胃炎患者病情较稳定,特别是不伴有H.pylori持续感染者。某些患者随着年龄增加,因衰老而出现萎缩等组织病理学改变[135,136]。更新的观点认为无论年龄,持续H.pylori感染均可能导致慢性萎缩性胃炎。

同一年龄者胃黏膜的衰老程度不尽相同,即可有不同的"胃龄";后者可依据胃黏膜细胞端粒的长度进行测定、计算[137]。实际年龄与"胃龄"差大者,可能更需要密切随访。

3.慢性萎缩性胃炎尤其是伴有中重度肠化生或上皮内瘤变者,要定期内镜、病理组织学检查和随访。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:97.1%。

一般认为,中、重度慢性萎缩性胃炎有一定的癌变率[138]。为了既减少胃癌的发生,又方便患者且符合医药经济学要求,活检有中-重度萎缩并伴有肠化生的慢性萎缩性胃炎患者需1年左右随访1次,不伴有肠化生或上皮内瘤变的慢性萎缩性胃炎患者可酌情内镜和病理随访[139]。伴有低级别上皮内瘤变并证明此标本并非来于癌旁者,根据内镜和临床情况缩短至6个月左右随访1次;而高级别上皮内瘤变需立即确认,证实后行内镜下治疗或手术治疗[76,77]。

为了便于对病灶监测、随访,有条件时可考虑进行有目标的光学活检或胃黏膜定标活检(mucosa target biopsy,MTB)[140,141],以提高活检阳性率和监测随访的准确性。但需指出的是,萎缩病灶呈"灶状分布" ,原定标部位变化不等于未定标部位变化。不能简单拘泥于与上次活检部位的一致性而忽视了新发病灶的活检。目前认为萎缩/肠化生的范围是判断严重程度的重要指标,这是定标不能反映的。

4.OLGA和OLGIM分级分期系统能反映胃炎患者的胃黏膜萎缩程度和范围,较有利于胃癌风险分层。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:92.8%。

2005年国际萎缩研究小组提出胃黏膜炎性反应、萎缩程度和范围的分级、分期标准(即慢性胃炎OLGA分级分期系统)[36],基于胃炎新悉尼系统对炎性反应和萎缩程度的半定量评分方法,采用胃炎分期代表胃黏膜萎缩范围和程度,将慢性胃炎的组织病理学与癌变危险性联系起来,为临床医师预测病变进展和制定疾病管理措施提供更为直观的信息。Rugge等[142]对93例慢性胃炎进行了12年的随访,发现绝大部分OLGA 0至Ⅱ期患者的胃炎分期维持不变,而癌变均发生在OLGA Ⅲ、Ⅳ期的群体中。多项研究显示,肠型胃癌患者的OLGA分期较高(Ⅲ、Ⅳ期),而十二指肠溃疡和胃溃疡的OLGA分期主要在0至Ⅱ期和Ⅱ、Ⅲ期[3,143,144,145]。高危等级OLGA分期(Ⅲ、Ⅳ期)与胃癌高危密切相关,但是医师间判断的一致率相对较低。因此,2010年又提出根据胃黏膜肠化生的OLGIM分期标准[146]。与OLGA相比,OLGIM分期系统则有较高的医师间诊断一致率,但是一些潜在的胃癌高危个体有可能被遗漏[147]。研究显示,与OLGA相比,OLGIM可使大约1/3病例的分期下调;按OLGA分期定为高危的病例中,小于1/10的病例则被OLGIM分期定为低危[148],因此,OLGIM低危等级不可等同于胃癌发生低危。

国内研究显示,胃癌组与非胃癌组OLGA Ⅲ至Ⅳ期的比例分别是52.1%和22.4%,OLGIM Ⅲ至Ⅳ期的比例分别是42.3%和19.9%(P均<0.01)[149,150]。高OLGA分期患者更易检出上皮内瘤变和腺癌,OLGA分期能有效地根据胃癌风险程度将胃炎患者进行风险分层。

因此,OLGA分期系统使用简便,可反映萎缩性胃炎的严重程度和患癌风险,利于识别胃癌高危患者(OLGA/OLGIM Ⅲ、Ⅳ期),有助于早期诊断和预防。在临床实践中,推荐OLGA与OLGIM结合使用,可更精确地预测胃癌风险。

5.血清胃蛋白酶原(pepsinogen,PG)Ⅰ、Ⅱ以及促胃液素-17(gastrin-17)的检测可能有助于判断有无胃黏膜萎缩和程度。血清PGⅠ、PGⅡ、PGⅠ/PGⅡ比值联合抗H.pylori抗体检测有助于风险分层管理。

推荐强度:条件。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:84.1%。

PG水平反映胃黏膜的功能状态,当胃黏膜出现萎缩时,PGⅠ和PGⅡ水平下降,PGⅠ水平下降更明显,因而PGⅠ/PGⅡ比值随之降低。PG测定有助于判断萎缩的范围[151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159]。胃体萎缩者PGⅠ、PGⅠ/PGⅡ比值降低,血清促胃液素-17水平升高;胃窦萎缩者,血清促胃液素-17水平降低,PGⅠ、PGⅠ/PGⅡ比值正常;全胃萎缩者则两者均降低。通常以PGⅠ水平≤70 g/L且PGⅠ/PGⅡ比值≤3.0作为萎缩性胃炎的诊断临界值,并以此作为胃癌高危人群筛查的标准 [160]在欧洲和日本广泛用于胃癌风险的筛查;国内胃癌高发区筛查常采用PGⅠ水平≤70 g/L且PGⅠ/PGⅡ≤7.0的标准[161],目前尚缺乏大样本的随访数据加以佐证。

多项研究证明,血清PG检测有助于胃癌高危人群的风险分层[162,163,164],PG检测诊断萎缩者,以及PG检测虽诊断萎缩阴性但PGⅠ/PGⅡ比值较低者,有较高的胃癌风险,应进一步进行胃镜检查。血清PG联合血清抗H.pylori抗体检测可将人群分为A、B、C、D 4组,不同组别其胃癌的发生率不同,是一项有价值的胃癌风险的预测指标,日本以此作为胃癌风险的分层方法(ABCD法),制定相应的检查策略[165,166,167,168,169]。最近国内的研究结果显示,PG、促胃液素-17和抗H.pylori抗体联合检测可对胃癌发生风险加以分层,辨识出高危个体进行胃镜检查[170]。

PGⅠ/PGⅡ比值与OLGA分期呈负相关[142,171],比值越低,分期越高,以PGⅠ/PGⅡ比值≤3.0为界可区别低危和高危OLGA分期,其敏感度为77%,特异度为85%,阳性预测值为45%,阴性预测值高达96%。H.pylori感染可致PGⅠ、PGⅡ水平升高,尤其是PGⅡ更明显,因此PGⅠ/PGⅡ比值下降,根除H.pylori后则PGⅠ、PGⅡ水平下降,PGⅠ/PGⅡ比值上升。

6.根除H.pylori可减缓炎性反应向萎缩、肠化生甚至异型增生的进程和降低胃癌发生率,但最佳的干预时间为胃癌前变化(包括萎缩、肠化生和上皮内瘤变)发生前。

推荐强度:强烈。证据质量:高。陈述同意率:92.7%。

较多研究发现,H.pylori感染有促进慢性萎缩性胃炎发展为胃癌的作用[172]。根除H.pylori可以明显减缓癌前病变的进展,并有可能减少胃癌发生的危险[173,174,175]。《H.pylori胃炎京都全球共识意见》特别倡导根除H.pylori预防胃癌[2]。

新近发表的一项根除H.pylori后随访14.7年的研究报告称,H.pylori根除治疗组(1 130例)和安慰剂组(1 128例)胃癌的发生率分别是3.0%和4.6% [176]。随访时间越长,则对胃癌的预防效果越佳,即便根除H.pylori时已经进入肠化生或上皮内瘤变阶段,亦有较好的预防作用[177]。

根除H.pylori对于轻度慢性萎缩性胃炎将来的癌变具有较好的预防作用[178]。根除H.pylori对于癌前病变病理组织学的好转有利[179]。且根除后,环氧合酶2表达和Ki-67指数均下降,前列腺素E2下调[180]。Meta分析显示,与欧美国家相比,包括我国等在内的东亚国家根除H.pylori以预防胃癌更符合卫生经济学标准[181]。

7.某些维生素可能有助于延缓萎缩性胃炎的进程,从而降低癌变风险。

推荐强度:条件。证据质量:中等。陈述同意率:87.0%。

某些维生素和微量元素硒可能降低胃癌发生的危险度[176,177,182,183,184,185,186,187]。但一项队列研究(并非随机对照试验研究)显示多种维生素并没有降低胃癌发生率[188]。对于部分体内低叶酸水平者,适量补充叶酸可改善慢性萎缩性胃炎病理组织状态而减少胃癌的发生[189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197]。

执笔撰写者(按撰写内容排序):房静远,杜奕奇,刘文忠,任建林,李延青,陈晓宇,吕农华,陈萦晅,吕宾

参与讨论和定稿者(按姓氏汉语拼音排序):白飞虎,白文元,陈红梅,陈旻湖,陈其奎,陈世耀,陈卫昌,陈晓宇,陈萦晅,杜奕奇,段丽平,房殿春,房静远,高峰,郜恒骏,戈之铮,郭晓钟,韩英,郝建宇,侯晓华,霍丽娟,纪小龙,姜泊,蒋明德,蓝宇,李建生,李景南,李良平,李岩,李延青,林琳,刘诗,刘思德,刘文忠,刘玉兰,陆伟,罗和生,吕宾,吕农华,钱家鸣,任建林,沈锡中,盛剑秋,时永全,苏秉忠,唐承薇,唐旭东,田德安,田字彬,庹必光,王邦茂,王吉耀,王江滨,王良静,王巧民,王蔚虹,王小众,王学红,韦红,吴开春,吴小平,谢渭芬,许建明,杨云生,游苏宁,张军,张澍田,张晓岚,张志广,郑鹏远,周丽雅,朱萱,邹多武,邹晓平

学术秘书:高琴琰

活检取材块数和部位由内镜医师根据需要决定,一般为2~5块。如取5块,则胃窦2块取自距幽门2~3 cm处的大弯和小弯,胃体2块取自距贲门8 cm处的大弯(约胃体大弯中部)和距胃角近侧4 cm处的小弯,胃角1块。

标本要足够大,达到黏膜肌层,对可能或肯定存在的病灶要另取标本。不同部位的标本须分开装瓶,并向病理科提供取材部位、内镜所见和简要病史。

有5种组织学变化要分级(H.pylori、慢性炎性反应、活动性、萎缩和肠化生),分成无、轻度、中度和重度4级(0、+、++、+++)。分级方法用下述标准,与悉尼系统的直观模拟评分法并用,病理检查要报告每块活检标本的组织学变化。

观察胃黏膜黏液层、表面上皮、小凹上皮和腺管上皮表面的H.pylori。无:特殊染色片上未见H.pylori。轻度:偶见或小于标本全长1/3有少数H.pylori。中度:H.pylori分布超过标本全长1/3而未达2/3或连续性、薄而稀疏地存在于上皮表面。重度:H.pylori成堆存在,基本分布于标本全长。肠化生黏膜表面通常无H.pylori定植,宜在非肠化生处寻找。

对炎性反应明显而H-E染色切片未发现H.pylori者,要行特殊染色仔细寻找,推荐用较简便的吉姆萨染色,也可按各病理室惯用的染色方法,有条件的单位可行免疫组织化学检测。

慢性炎性反应背景上有中性粒细胞浸润。轻度:黏膜固有层有少数中性粒细胞浸润。中度:中性粒细胞较多存在于黏膜层,可见于表面上皮细胞、小凹上皮细胞或腺管上皮内。重度:中性粒细胞较密集,或除中度所见外还可见小凹脓肿。

根据黏膜层慢性炎细胞的密集程度和浸润深度分级,前者更重要。正常:单个核细胞每个高倍视野不超过5个,如数量略超过正常而内镜下无明显异常,病理可诊断为基本正常。轻度:慢性炎细胞较少并局限于黏膜浅层,不超过黏膜层的1/3。中度:慢性炎细胞较密集,不超过黏膜层的2/3。重度:慢性炎细胞密集,占据黏膜全层。计算密度程度时要避开淋巴滤泡及其周围的小淋巴细胞区。

萎缩是指胃固有腺的减少,分为2种情况。①化生性萎缩,胃固有腺被肠化生或假幽门腺化生的腺体替代;②非化生性萎缩,胃固有腺被纤维或纤维肌性组织替代,或炎性细胞浸润引起固有腺数量减少。

萎缩程度以胃固有腺减少各1/3来计算。轻度:固有腺体数减少不超过原有腺体的1/3。中度:固有腺体数减少介于原有腺体的1/3~2/3之间。重度:固有腺体数减少超过2/3,仅残留少数腺体,甚至完全消失。局限于胃小凹区域的肠化生不算萎缩。黏膜层出现淋巴滤泡不算萎缩,要观察其周围区域的腺体情况来决定。一切原因引起黏膜损伤的病理过程都可造成腺体数量减少,如溃疡边缘取的活检,不一定就是萎缩性胃炎。

标本过浅未达黏膜肌层者,可以参考黏膜层腺体大小、密度和间质反应情况推断是否萎缩,同时加上评注取材过浅的注释,提醒临床只供参考。

肠化生区占腺体和表面上皮总面积1/3以下为轻度,1/3~2/3为中度,2/3以上为重度。AB-PAS染色对不明显肠化生的诊断很有帮助。用AB-PAS和HID-AB黏液染色区分肠化生亚型预测胃癌发生危险性的价值仍有争议。

出现不需要分级的组织学变化时需注明。分为非特异性和特异性两类,前者包括淋巴滤泡、小凹上皮增生、胰腺化生和假幽门腺化生等;后者包括肉芽肿、集簇性嗜酸性粒细胞浸润、明显上皮内淋巴细胞浸润和特异性病原体等。假幽门腺化生是泌酸腺萎缩的指标,判断时要核实取材部位,胃角部活检见到黏液分泌腺的不能诊断为假幽门腺化生,只有出现肠化生,才是诊断萎缩的标志。

有异型增生(上皮内瘤变)时要注明,分轻度、中度和重度异型增生(或低级别和高级别上皮内瘤变)。

慢性胃炎分为非萎缩性胃炎和萎缩性胃炎两类,按照病变的部位分为胃窦胃炎、胃体胃炎和全胃炎。有少部分是特殊类型胃炎,如化学性胃炎、淋巴细胞性胃炎、肉芽肿性胃炎、嗜酸细胞性胃炎、胶原性胃炎、放射性胃炎、感染性(细菌、病毒、真菌和寄生虫)胃炎和Ménétrier病。

诊断应包括部位分布特征和组织学变化程度,有病因可循的要报告病因。胃窦和胃体炎性程度相差2级或以上时,加上"为主"修饰词,如"慢性(活动性)胃炎,胃窦为主"。

萎缩性胃炎的诊断标准:只要慢性胃炎的病理活检显示固有层腺体萎缩即可诊断萎缩性胃炎,而不管活检标本的萎缩块数和程度。临床医师可根据病理结果并结合内镜所见,最后做出萎缩范围和程度的判断。

| 现行的国际疾病分类第10版胃炎分类 | 《幽门螺杆菌胃炎京都全球共识意见》提议胃炎的病因学分类 | 正在讨论中的国际疾病分类第11版β胃炎分类(2017年6月25日更新) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K29胃炎和十二指肠炎 | 自身免疫性胃炎 | 外在因素引起的胃炎 | 自身免疫性胃炎 | 外在因素引起的胃炎 | |||||||

| 排除:嗜酸性胃炎或胃肠炎 (K52.8) | 感染性胃炎 | 药物性胃炎 | 幽门螺杆菌性胃炎 | 酒精性胃炎 | |||||||

| 幽门螺杆菌性胃炎 | 酒精性胃炎 | 嗜酸细胞性胃炎 | 放射性胃炎 | ||||||||

| Zollinger-Ellison综合征(E16.4) | 除幽门螺杆菌外其 | 放射性胃炎 | 食物诱导的嗜酸细胞性胃肠炎 | 化学性胃炎 | |||||||

| K29.0急性出血性胃炎 | 他细菌性胃炎 | 化学性胃炎 | 淋巴细胞性胃炎 | 其他特殊性外在因素引起 的胃炎 | |||||||

| 包括急性(糜烂性)胃炎伴出血 | 海尔曼螺杆菌性 | 十二指肠反流性胃炎 | 变应性胃炎 | ||||||||

| 排除胃糜烂(急性)(K25.-) | 胃炎 | 其他特殊性外在 | IgE介导的过敏反应引起的变 应性胃炎 | 药物性胃炎 | |||||||

| K29.1其他急性胃炎 | 肠球菌性胃炎 | 因素引起的胃炎 | 其他疾病相关性胃炎 | ||||||||

| K29.2酒精性胃炎 | 分支杆菌性胃炎 | 特殊性胃炎 | 食物诱导的IgE介导的胃肠道过敏反应 | 克罗恩病相关性胃炎 | |||||||

| K29.3慢性浅表性胃炎 | 二期梅毒性胃炎 | 淋巴细胞性胃炎 | 结节病相关性胃炎 | ||||||||

| K29.4慢性萎缩性胃炎 | 胃蜂窝织炎 | Ménétrier病 | 非IgE介导的过敏反应引起的 变应性胃炎 | 血管炎相关性胃炎 | |||||||

| 包括胃萎缩 | 病毒性胃炎 | 变应性胃炎 | 胃蜂窝织炎 | ||||||||

| K29.5慢性胃炎,非特异性 | 肠病毒性胃炎 | 嗜酸性胃炎 | 食物诱导的非IgE介导的胃肠 道过敏反应 | ||||||||

| 包括慢性胃窦炎 | 巨细胞病毒性胃炎 | 其他疾病相关性胃炎 | |||||||||

| 慢性胃底炎 | 真菌性胃炎 | 结节病相关性胃炎 | 十二指肠胃反流引起的胃炎 | ||||||||

| K29.6其他类型胃炎 | 毛霉菌性胃炎 | 血管炎相关性胃炎 | Ménétrier病 | ||||||||

| 包括肥厚性胃炎 | 胃念珠菌病 | 克罗恩病相关性胃炎 | 未知病因引起的特异性内镜 | ||||||||

| 肉芽肿性胃炎 | 胃组织胞浆菌病 | 表现或病理表现的胃炎 | |||||||||

| Ménétrier病(胃巨皱襞症) | 寄生虫性胃炎 | 急性浅表性胃炎 | |||||||||

| K29.7胃炎,非特异性 | 隐孢子虫性胃炎 | 慢性浅表性胃炎 | |||||||||

| K29.8十二指肠炎 | 胃粪类圆线虫病 | 急性出血性胃炎 | |||||||||

| K29.9胃十二指肠炎,非特异性 | 胃异尖线虫病 | 慢性萎缩性胃炎 | |||||||||

| 轻中度胃萎缩 | |||||||||||

| 重度胃萎缩 | |||||||||||

| 化生性胃炎 | |||||||||||

| 肉芽肿性胃炎 | |||||||||||

| 肥厚性胃炎 | |||||||||||