呼吸道合胞病毒(respiratory syncytial virus, RSV)是急性呼吸道感染的主要病原体之一,给全世界造成了巨大的负担。病毒与宿主细胞受体识别和相互作用,是建立感染的关键初始步骤,受体分布影响病毒的细胞嗜性和组织嗜性,影响病毒在宿主体内的复制和增殖。但目前RSV受体尚不明确,这也是阻碍RSV疫苗及治疗性药物研发的原因之一。本文通过对现有的RSV受体进行综述,以期对RSV疫苗及治疗性药物的研发提供思路。

版权归中华医学会所有。

未经授权,不得转载、摘编本刊文章,不得使用本刊的版式设计。

除非特别声明,本刊刊出的所有文章不代表中华医学会和本刊编委会的观点。

呼吸道合胞病毒(respiratory syncytial virus, RSV),是副黏病毒科正肺病毒属的非分节段的单股负链RNA病毒,是一种多形病毒颗粒,主要通过唾液和飞沫传播[1],是全球呼吸道疾病(lower respiratory tract illness, LRTI)的重要病原体。60%以上的儿童急性呼吸道感染和80%以上的婴幼儿肺炎及支气管炎都与RSV感染有关[2],老年人和有基础疾病的患者感染RSV也会患上严重的急性呼吸道疾病[3]。

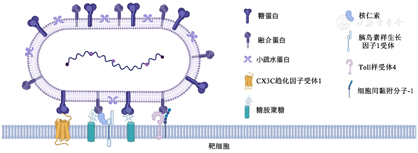

RSV基因组全长约15.2 kb,包括10个开放阅读框,编码11种蛋白质,其中包膜外侧的跨膜糖蛋白(glycoprotein, G)和融合蛋白(fusion protein, F)对于RSV的黏附、入胞和合胞体形成十分重要[4]。RSV感染细胞通常包括病毒附着和融合两个过程。RSV主要通过G蛋白黏附在宿主鼻腔纤毛上皮细胞表面[5], F蛋白介导病毒囊膜与宿主膜的融合,并将核衣壳释放到宿主细胞质[6]。病毒进入细胞后,在大聚合酶蛋白(large polymerase protein, L)、核蛋白(nucleoprotein, N)和磷蛋白(phosphoprotein, P)的共同作用下,负链RNA转录为mRNA,后者编码病毒蛋白质。病毒跨膜蛋白经翻译后修饰,由分泌膜系统转运至细胞膜,在细胞膜上与N蛋白、P蛋白、基质蛋白(matrix protein, M)及病毒基因组RNA组成的核糖核蛋白(ribonucleoprotein, RNP)相互作用[7],随后病毒组装成球形或丝状的成熟多形病毒颗粒[8]。

目前已知的参与RSV附着和融合过程的受体和信号通路比较复杂(图1),以下对其受体及机制进行综述。

G蛋白是参与RSV附着的主要蛋白质。在RSV感染后会产生两种形式的G蛋白:一种是全长的膜结合型G蛋白(membrane-bound glycoprotein, mG),是参与病毒附着过程的主要G蛋白形式[9];另一种是分泌型G蛋白(soluble form glycoprotein, sG),sG是由G蛋白跨膜区的AUG起始翻译而产生的,在感染后12 h即可检测到,其可能在感染过程中起到抗原诱饵的作用[10],降低RSV抗体介导的中和效率。参与病毒附着过程的mG胞外结构域包括两个高度可变的糖基化结构域(aa 66~160;aa 192~319)和一个中央保守结构域(central conserved domain, CCD, aa 160~200),两个糖基化结构域位于CCD的两侧[11]。CCD结构域在A型和B型RSV中相对保守,含有在所有毒株中保守的13个氨基酸(aa 164~176)、一个CX3C趋化因子基序(aa 182~186)以及位于aa 184~198的肝素结合域(heparin-binding domain, HBD)[12]。G蛋白CX3C趋化因子结构域可能通过模拟趋化因子CX3C配体(CX3C ligend, CX3CL),介导病毒与细胞表面趋化因子CX3C受体1(CX3C receptor 1, CX3CR1)相互作用;HBD结构域带大量正电荷[12],可能参与了与硫酸乙酰肝素(heparan sulfate, HS)和其他糖胺聚糖(glycosaminoglycans,GAGs)的相互作用。

CX3C基序受体CX3CR1是一种七跨膜G偶联趋化因子受体,可在多种细胞中表达,肺部只在肺纤毛上皮细胞的运动纤毛上表达[13]。RSV G蛋白的CX3C趋化因子基序和CX3CL是CX3CR1仅有的两个已知配体[14]。Tripp等[14]在纯化的人外周血单核细胞培养过程中加入G蛋白和CX3CL,可以检测到向G蛋白和CX3CL迁移的CX3CR1+白细胞百分比上升,且G蛋白和CX3CL对白细胞的趋化作用可以相互拮抗。

在1月龄健康婴儿的上呼吸道基因表达数据库中,大多数受试者都能检测到CX3CR1转录本,免疫组化也检测到气道上皮细胞CX3CR1蛋白的表达,但CX3CR1绝对表达水平差异很大[15]。Anderson等[15]使用气液界面培养原代小儿肺上皮细胞(primary pediatric human lung epithelial cell, PHLE),发现PHLE细胞培养物中CX3CR1表达水平高于Hep-2细胞,在RSV感染后的PHLE细胞中CX3CR1转录水平最高,这在一定程度上说明RSV可能优先靶向表达CX3CR1的细胞。另外,蛋白质水平研究表明,CX3CR1在棉鼠与人类中的同源性达到90%[16],Chen等[17]证明,CX3CR1与CX3CL结合所必需的7个氨基酸在人类、棉鼠和小鼠间是保守的。对棉鼠的肺部和鼻部进行免疫组化染色发现,RSV感染发生在CX3CR1染色阳性的细胞中,且针对RSV G蛋白的抗体可预防棉鼠感染RSV,体内实验也证明降低CX3CR1的表达可减少棉鼠感染RSV[18]。

尽管抗CX3CR1抗体能降低RSV感染的病毒载量,但不能完全消除RSV的复制,这说明除通过G蛋白与CX3CR1结合外,RSV还可能通过其他蛋白质和相应受体感染细胞,如F蛋白等,这与缺乏G蛋白的RSV病毒仍能感染某些细胞和动物的报道[19,20,21]相一致。

GAGs也称黏多糖,是普遍存在于细胞表面和细胞外基质中的带负电荷的复杂多糖,存在不同程度的磷酸化[22]。根据其化学结构,一般将GAGs分为4个家族:透明质酸(hyaluronic acid, HA)、肝素(heparin, HP)/硫酸乙酰肝素(heparan sulfate, HS)、硫酸软骨素(chondroitin salfate, CS)/硫酸硬骨素(dermatan sulfate, DS)和硫酸角质素(keratan sulfate, KS)。许多病原体通过表达GAGs结合蛋白促进病毒与宿主细胞的结合,例如人类偏肺病毒(human metapneumovirus, hMPV)的F蛋白[23]和G蛋白[24]可以介导病毒附着在细胞表面的GAGs上(尤其是细胞表面的硫酸乙酰肝素)。

有体外实验已经证明,肝素和硫酸乙酰肝素在RSV与宿主细胞相互作用中发挥着重要的辅助受体作用。RSV的F蛋白和G蛋白中带正电的碱性氨基酸[12,13]与细胞表面的硫酸乙酰肝素中带负电荷的硫酸基团及羧基相互作用。有研究者通过表面等离子共振(surface plasmon resonance, SPR)技术研究了RSV F蛋白和G蛋白与肝素结合的亲和力和动力学特征,结果发现,G蛋白和F蛋白与肝素的结合亲和力极高,但F蛋白与肝素的亲和力更强[25]。另外,通过G蛋白上的HBD,RSV可能与永生化细胞表面的GAGs结合[12],促进永生化细胞的感染,但也有观点认为,硫酸乙酰肝素仅在永生化细胞,如Hep-2细胞等表面表达丰富,在分化良好的原代纤毛上皮细胞的顶端没有检测到硫酸乙酰肝素[26],而纤毛上皮细胞是RSV在体内复制的主要场所[27]。这可能表明硫酸乙酰肝素在RSV感染人体细胞中的作用和机制还需要进一步确认。

F蛋白也能促进病毒附着,但程度不如G蛋白,其主要负责病毒对宿主细胞的融合以及随后的细胞间传播或合胞体形成[28]。RSV F基因编码非融合活性前体F蛋白F0,F0组装成一个同源三聚体。当F0三聚体经过高尔基体时,F蛋白被呋喃样蛋白酶裂解,裂解产物包括N端的F2亚基和C端的F1亚基,以及一个由27个氨基酸残基组成的多肽片段(27-amino-acid peptide, p27),F1亚基和F2亚基通过二硫键连接,形成亚稳态的融合前F蛋白(PreF)[29]。F1亚基的N端有疏水性的融合肽,当RSV与宿主细胞膜靠近时,融合肽的α-螺旋区(α-helical region A, HRA)伸展,插入靶细胞膜,然后3个F1单体自身折叠,HRA与F1跨膜结构域附近的第2个α-螺旋区(α-helical region B, HRB)并列排列,形成高度稳定的六螺旋束(six-helix bundle, 6HB),该过程将病毒包膜与靶细胞膜拉在一起以启动膜融合[30],PreF转变为稳定的融合后F蛋白(PostF)。两种F蛋白构象有不同的抗原表位:PreF有Ⅰ、Ⅱ、Ⅲ、Ⅳ、Ⅴ和六种抗原表位,而PostF中只有Ⅰ、Ⅱ、Ⅲ和Ⅳ四种抗原表位,其中PreF特有的抗原表位诱导中和抗体能力高于其他抗原表位[31]。理想情况下,为了防止病毒的进入,需要以PreF构象作为抗原表位开发药物或疫苗。

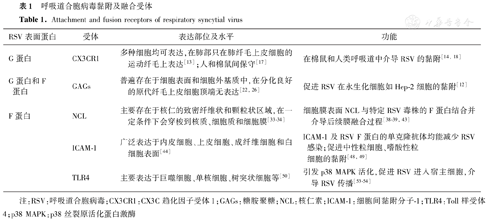

目前已报道的参与融合过程的受体包括核仁素(nucleolin, NCL)、GAGs、Toll样受体4(Toll-like receptor 4, TLR4)、表皮生长因子受体(epithelial growth factor receptor, EGFR)、细胞间黏附分子-1(intercellular adhension molecular-1, ICAM-1)等(表1)。

呼吸道合胞病毒黏附及融合受体

Attachment and fusion receptors of respiratory syncytial virus

呼吸道合胞病毒黏附及融合受体

Attachment and fusion receptors of respiratory syncytial virus

| RSV表面蛋白 | 受体 | 表达部位及水平 | 功能 |

|---|---|---|---|

| G蛋白 | CX3CR1 | 多种细胞均可表达,在肺部只在肺纤毛上皮细胞的运动纤毛上表达[13];人和棉鼠间保守[17] | 在棉鼠和人类呼吸道中介导RSV的黏附[14,18] |

| G蛋白和F蛋白 | GAGs | 普遍存在于细胞表面和细胞外基质中,在分化良好的原代纤毛上皮细胞顶端无表达[22,26] | 促进RSV在永生化细胞如Hep-2细胞的黏附[12] |

| F蛋白 | NCL | 主要存在于核仁的致密纤维状和颗粒状区域,在一定条件下会穿梭到核质、细胞质和细胞膜[33,34] | 细胞膜表面NCL与特定RSV毒株的F蛋白结合并介导后续膜融合过程[38,39,43] |

| ICAM-1 | 广泛表达于内皮细胞、上皮细胞、成纤维细胞和白细胞表面[44] | ICAM-1及RSV F蛋白的单克隆抗体均能减少RSV感染;促进中性粒细胞、嗜酸性粒细胞的黏附[48,49] | |

| TLR4 | 主要表达于巨噬细胞、单核细胞、树突状细胞等[50] | 引发p38 MAPK活化,促进RSV进入宿主细胞,介导RSV传播[53,54] |

注:RSV:呼吸道合胞病毒;CX3CR1:CX3C趋化因子受体1;GAGs:糖胺聚糖;NCL:核仁素;ICAM-1:细胞间黏附分子-1;TLR4:Toll样受体4;p38 MAPK:p38丝裂原活化蛋白激酶

NCL是一种参与多个细胞过程的多功能蛋白质,有3个结构域:N端富含谷氨酸和天冬氨酸,主要参与细胞分化调控;C端主要与核苷酸相互作用,促进RNA与中部RNA结合结构域的结合[32]。NCL在进化过程中高度保守,主要存在于核仁的致密纤维状和颗粒状区域,但在一定条件下,NCL也会移动到细胞的其他区域,如核质、细胞质和细胞膜[33,34],如在肿瘤生长过程中,NCL会从细胞核穿梭到细胞表面,成为细胞外配体的靶标[35]。在病毒感染过程中,NCL似乎也发挥了一定的作用。横纹肌肉瘤(rhabdomyosarcoma, RD)细胞是肠道病毒71型(enterovirus 71, EV71)的易感细胞,有研究者使用共聚焦显微镜观察到NCL与EV71在RD细胞表面的共定位,将RD细胞表面NCL敲低,EV71与细胞的结合能力减弱,感染能力下降[34];Chan等[36]发现无论是用NCL抗体抑制细胞表面NCL,还是用纯化的NCL与A/Puerto Rico/8/34(H1N1)株流感病毒(简称PR8流感病毒)孵育,都能显著减少PR8流感病毒的内化,除PR8流感病毒外,该研究者还验证了NCL对H1N1、H3N1、H5N1和H7N9内化的作用,均得到相同的结论;在人类副流感病毒3型(human parainfluenza virus type 3, HPIV-3)中也发现细胞表面NCL是病毒内化过程的重要蛋白质[37]。以上研究结果提示细胞表面的NCL可能促进病毒颗粒的附着或进入宿主细胞膜。

在RSV感染过程中也发现了与细胞表面NCL的相互作用。RSV F糖蛋白与胰岛素样生长因子1受体(IGF1R)结合引发了蛋白激酶C-ζ(protein kinase C ζ,PKCζ)的活化,NCL通过这种活化作用从细胞核被招募到细胞膜,在细胞膜上与RSV F蛋白结合并介导后续膜融合的过程[38]。在病毒感染细胞前加入NCL特异性抗体,几乎能够完全消除RSV和NCL在细胞表面的共定位情况[39]。另外,NCL-siRNA、由NCL RNA识别基序中的两个12 bp片段衍生的合成肽[40]或能与NCL结合的非编码单链寡核苷酸[41]都能抑制RSV体外感染。

据报道,肝素等可溶性GAGs能与NCL结合[42],因此肝素可能会与RSV竞争结合细胞表面的NCL。在进一步的研究中,Holguera等[43]发现肝素会减弱RSV与NCL的结合,而Tayyari等[39]则发现肝素不会干扰RSV F蛋白与NCL的相互作用。出现这种差异的原因可能是两篇文章中测试了不同基因型的RSV毒株,Holguera等[43]使用的是A亚型中的Long基因型,而Tayyari等[39]使用的是A亚型中的A2基因型。A2基因型RSV病毒F蛋白的第213位氨基酸残基为丝氨酸,而Long基因型RSV病毒该位置的氨基酸为精氨酸,这两种氨基酸在中性环境中带电荷不同,精氨酸残基比丝氨酸残基更容易与肝素结合。这说明NCL可能是RSV F蛋白的相关受体,但是不同的RSV毒株与NCL的相互作用可能不同。

ICAM-1是免疫球蛋白超家族的成员之一,广泛表达于内皮细胞、上皮细胞、成纤维细胞和白细胞表面[44],在炎症过程中ICAM-1可以将白细胞从血液循环招募到炎症部位;在病毒感染过程中,病毒与细胞外结构域结合后,ICAM-1通过其胞质结构域与肌动蛋白细胞骨架的结合传递外来信号[45],启动T细胞和巨噬细胞等细胞的活化。有研究显示,鼻病毒感染后通过诱导上皮细胞表达IL-6促进ICAM-1表达[46],从而促使鼻病毒以ICAM-1作为受体附着并进入上皮细胞[47]。

ICAM-1和RSV被证明在Hep-2细胞表面存在共定位,研究者发现,在RSV感染后24 h和48 h,细胞表面ICAM-1的表达分别增加了4倍和8倍;用不同浓度的抗ICAM-1的单克隆抗体可以阻断上皮细胞的ICAM-1,减少RSV感染;研究者通过将RSV病毒与F蛋白的单克隆抗体孵育后,发现RSV与ICAM-1的结合能力减少了80%[48]。这在一定程度上说明ICAM-1是RSV的一种潜在受体。另外,被RSV感染后的呼吸道上皮细胞ICAM-1表达上调,促进了中性粒细胞、嗜酸性粒细胞的黏附,这很可能是引起气道炎症和损伤的原因[49]。

TLR4是一种保守的固有免疫受体,主要表达在巨噬细胞、单核细胞、树突状细胞等细胞的细胞膜上[50],可以识别病原体相关分子模式(pathogen-associated molecular patterns, PAMPs)、损伤相关分子模式(damage-associated molecular patterns, DAMPs)和异生物相关分子模式(xenobiotic-associated molecular patterns, XAMPs),脂多糖是TLR4的典型配体[51]。

RSV F蛋白与宿主纤毛支气管上皮细胞上表达的TLR4结合[52],并在进入过程中引发p38丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases, p38 MAPK)的活化,从而增强RSV进入宿主细胞的能力,如果在病毒接种前用抗体阻断TLR4,不仅可以抑制病毒诱导的p38 MAPK激活,还能抑制RSV和流感病毒的感染[53]。但是,由于TLR4在感染RSV后才会在人类支气管上皮细胞(human bronchial epithelial cells, NHBE)中表达[54],因此TLR4可能在宿主感染病毒后病毒传播过程中发挥作用。

临床针对RSV感染主要的治疗措施为支气管扩张剂、肾上腺素、皮质类固醇和高渗盐水等对症支持治疗,仍缺乏特异性抗病毒药物和疫苗等治疗和预防措施。帕利珠单抗(Palivizumab)是一种针对RSV F蛋白的人源化单克隆抗体,能特异性抑制RSV A和B亚型F蛋白融合前和融合后构象的Ⅱ抗原位点[55],在预防性给药时可降低体内的RSV载量,从而抑制病毒复制[56],1998年被批准用于预防具有某些危险因素的幼儿因RSV引起的下呼吸道疾病(LRTD)[57]。目前,颗粒疫苗、载体疫苗、减毒活疫苗、亚单位疫苗和mRNA疫苗等5条技术路线的RSV疫苗正在开发[58]。2023年,FDA新批准了Nirsevimab单抗(Beyfortus)和RSV PreF3 OA疫苗(Arexvy),用于预防RSV感染引起的LRTD[59]。其中Nirsevimab是一种重组IgG κ单克隆抗体,可在高度保守的表位上结合RSV F蛋白的F1和F2亚基,并将RSV F蛋白锁定在PreF构象,发挥中和RSV病毒的功能,以阻止病毒进入宿主细胞[60]。RSV PreF3 OA (Arexvy)疫苗以AS01E为佐剂辅佐等量的RSV A亚型和B亚型病毒PreF蛋白[61],能够激发机体产生针对RSV A亚型和B亚型两种亚型的免疫应答[59]。RSV F蛋白相对保守,且自然感染引起的RSV中和抗体靶点主要位于RSV PreF构象上,所以目前RSV疫苗的开发主要集中在F蛋白。但是除F蛋白外,还有G或者其他潜在的与细胞受体结合的靶抗原可能有助于提高RSV疫苗的疗效,因此对RSV及其受体的研究或许会推进更为有效的预防手段的开发。

病毒与细胞受体的识别和相互作用是病毒传染性生命周期中的第一步,在病毒感染的组织嗜性和致病过程中起着关键的作用[62]。但由于RSV潜在受体种类众多,多数受体并不是病毒进入宿主的唯一途径,并且不同RSV毒株之间与受体的作用可能也不尽相同,这极大的限制了受体靶点在RSV治疗药物和疫苗开发中的应用。除此之外,大量证据显示,包括流感病毒和人类免疫缺陷病毒(human immunodeficiency virus, HIV)在内的病毒可通过非受体机制(如通过隧道纳米管)在细胞间传播[63,64],这也为RSV感染机制和受体发现提供另一种思路。

李淑艳,杨惠洁,权娅茹,等.呼吸道合胞病毒受体研究进展[J].中华微生物学和免疫学杂志,2024,44(2): 183-188. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112309-20240111-00019.

所有作者声明无利益冲突