分析儿童重症医学科(PICU)重症肺炎患儿死亡的危险因素,探讨改良PIRO(mPIRO)评分量表对死亡风险的预测价值,并适当改进。

病例对照研究。回顾性分析2015年5月至2021年12月重庆医科大学附属儿童医院PICU诊治的460例重症肺炎患儿的临床资料,以是否发生死亡将研究对象分为存活组(411例)和死亡组(49例)。采用Logistic回归分析PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡的危险因素,应用mPIRO评分量表评估其死亡风险,将量表中脉搏氧饱和度(SpO2)<0.90改进为SpO2与吸入气氧体积分数比值≤160形成改进后的评分量表,通过绘制受试者工作特征(ROC)曲线、校准曲线及决策曲线分析(DCA)比较2个评分量表的预测性能。

Logistic回归分析发现,发生低血压、急性肝衰竭、急性肾损伤、急性呼吸窘迫综合征及血糖升高是PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡的独立危险因素(均P<0.05)。ROC曲线分析显示,改进后的评分量表的曲线下面积为0.747,显著高于mPIRO评分量表的0.718(P<0.05);校准曲线显示,改进后的评分量表的预测结果与实际结果间的一致性更好,DCA显示当阈值概率为0.1~0.4时,改进后的评分量表的净获益高于mPIRO评分量表。

发生低血压、急性肝衰竭、急性肾损伤、急性呼吸窘迫综合征及血糖升高是PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡的独立危险因素,mPIRO评分量表及改进后的评分量表对PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡具有一定的预测价值,且改进后的评分量表更佳。

版权归中华医学会所有。

未经授权,不得转载、摘编本刊文章,不得使用本刊的版式设计。

除非特别声明,本刊刊出的所有文章不代表中华医学会和本刊编委会的观点。

肺炎是5岁以下儿童常见住院疾病及死亡的首要原因[1],我国儿童肺炎病死率从1996年的22.6%下降至2015年的12.2%,但每年仍有2.22万儿童死于肺炎[2]。在所有儿童社区获得性肺炎(community acquired pneumonia,CAP)中,5%的急诊病例、11.0%~12.5%的住院病例需入住儿童重症医学科(pediatric intensive care unit,PICU),且部分患儿发生死亡,占PICU死亡患儿的12%[3,4,5,6,7],因此早期识别PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡的危险因素,准确预测其死亡风险并积极采取有效的干预措施,有助于降低儿童肺炎的死亡率。

有关儿童CAP死亡风险的临床预测模型有改良PIRO(the modified predisposition,insult,response,and organ dysfunction,mPIRO)评分量表、儿童呼吸严重指数及儿童健康肺炎病因研究评分等[4,8,9,10,11,12,13],但大部分CAP死亡风险模型不适用于我国肺炎患儿,且外部验证后模型区分度不足[3,14],目前有关PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡风险因素的研究报道较少[15]。

mPIRO评分量表由Araya等[4]在成人PIRO模型的基础上结合儿童的特点改进形成,用于儿童CAP死亡风险评估,具有高度区分度[16]。本研究分析PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡的风险因素,探讨mPIRO评分量表在PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡风险预测方面的价值。由于PICU重症肺炎患儿往往用氧及合并严重的低氧血症,mPIRO评分量表中低氧即脉搏氧饱和度(pulse oxygen saturation,SpO2)<0.90不足以全面真实评估其氧合情况,同时为消除吸入气中氧体积分数(fraction of inspired oxygen,FiO2)对SpO2的影响,本研究将低氧调整为SpO2/FiO2(S/F)≤160形成改进后的mPIRO评分量表,将其与mPIRO评分量表进行比较,以期更好地指导PICU重症肺炎患儿的病情评估。

回顾性病例对照研究。选取2015年5月至2021年12月重庆医科大学附属儿童医院PICU诊治的460例重症肺炎患儿为研究对象。纳入标准:(1)28 d<年龄≤15岁;(2)符合《儿童社区获得性肺炎诊疗规范(2019年版)》中重症肺炎的诊断标准[17]。排除标准:(1)临床资料不完整的患儿;(2)放弃或拒绝治疗的患儿。将研究对象以是否发生死亡分为死亡组和存活组。

本研究通过重庆医科大学附属儿童医院医学伦理委员会批准[批准文号:(2023)年伦审(研)第(477)号],豁免患儿及其监护人知情同意。

收集儿童重症肺炎死亡相关的危险因素[4,8,9,10,18]:(1)一般资料:年龄、性别、早产史、基础疾病[19,20];(2)并发症:低血压[21]、急性肝衰竭(acute hepatic failure,AHF)[22,23]、急性肾损伤(acute kidney injury,AKI)[24]及急性呼吸窘迫综合征(acute respiratory distress syndrome,ARDS)[25];(3)入住PICU前后24 h内的实验室检查指标:白细胞计数、C反应蛋白、降钙素原、动脉氧分压(arterial partial pressure of oxygen,PaO2)/FiO2(P/F)、S/F、乳酸、血糖、丙氨酸转氨酶、天冬氨酸转氨酶,胸部影像学。多叶浸润指胸部影像学提示实变存在于1个以上肺叶;复杂性肺炎为胸部影像学显示存在胸腔积液、脓胸、气胸或脓气胸等[4]。

采用SPSS 26.0软件进行统计分析,定性资料采用例(%)表示,组间比较采用χ2检验或Fisher′s确切概率法;正态分布定量资料采用 ±s表示,组间比较采用独立样本t检验;非正态分布定量资料采用M(Q1,Q3)表示,组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验,相关性分析采用Spearman法分析,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。采用R 4.2.0软件进行Logistic回归分析发现危险因素,绘制受试者工作特征(receiver operator characteristic curve,ROC)曲线、校准曲线及临床决策曲线分析(decision curve analysis,DCA)评估模型的区分度、校准度及临床应用价值,净重新分类指数(net reclassification index,NRI)及综合判别改善指数(integrated discrimination improvement,IDI)评估改进后的mPIRO评分量表的改善程度[26],最终进行多模型比较,检验水准取α=0.05。

±s表示,组间比较采用独立样本t检验;非正态分布定量资料采用M(Q1,Q3)表示,组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验,相关性分析采用Spearman法分析,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。采用R 4.2.0软件进行Logistic回归分析发现危险因素,绘制受试者工作特征(receiver operator characteristic curve,ROC)曲线、校准曲线及临床决策曲线分析(decision curve analysis,DCA)评估模型的区分度、校准度及临床应用价值,净重新分类指数(net reclassification index,NRI)及综合判别改善指数(integrated discrimination improvement,IDI)评估改进后的mPIRO评分量表的改善程度[26],最终进行多模型比较,检验水准取α=0.05。

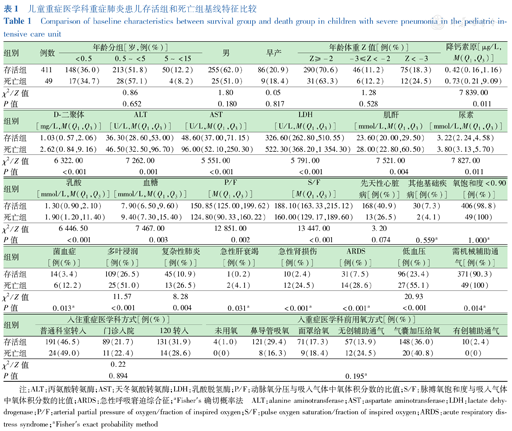

共纳入重症肺炎患儿460例,其中男280例(60.87%),女180例(39.13%);年龄9个月15 d(29 d至14岁11个月);早产95例(20.65%),死亡49例(10.65%)。存活组和死亡组年龄、性别及早产的差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。死亡组丙氨酸转氨酶、天冬氨酸转氨酶、乳酸脱氢酶、肌酐、尿素、D-二聚体、降钙素原、乳酸、血糖均高于存活组,P/F、S/F均低于存活组(均P<0.05)。存活组和死亡组发生菌血症、多叶浸润、复杂性肺炎、AHF、AKI、ARDS、低血压及入住PICU后需机械辅助通气的差异均有统计学意义(均P<0.05),结果见表1。

儿童重症医学科重症肺炎患儿存活组和死亡组基线特征比较

Comparison of baseline characteristics between survival group and death group in children with severe pneumonia in the pediatric intensive care unit

儿童重症医学科重症肺炎患儿存活组和死亡组基线特征比较

Comparison of baseline characteristics between survival group and death group in children with severe pneumonia in the pediatric intensive care unit

| 组别 | 例数 | 年龄分组[岁,例(%)] | 男 | 早产 | 年龄体重Z值[例(%)] | 降钙素原[μg/L,M(Q1,Q3)] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.5 | 0.5~<5 | 5~<15 | Z≥-2 | -3≤Z<-2 | Z<-3 | |||||

| 存活组 | 411 | 148(36.0) | 213(51.8) | 50(12.2) | 255(62.0) | 86(20.9) | 290(70.6) | 46(11.2) | 75(18.3) | 0.42(0.16,1.16) |

| 死亡组 | 49 | 17(34.7) | 28(57.1) | 4(8.2) | 25(51.0) | 9(18.4) | 31(63.3) | 6(12.2) | 12(24.5) | 0.73(0.21,9.09) |

| χ2/Z值 | 0.86 | 1.80 | 0.05 | 1.28 | 7 839.00 | |||||

| P值 | 0.652 | 0.180 | 0.817 | 0.528 | 0.011 | |||||

| 组别 | D-二聚体[mg/L,M(Q1,Q3)] | ALT[U/L,M(Q1,Q3)] | AST[U/L,M(Q1,Q3)] | LDH[U/L,M(Q1,Q3)] | 肌酐[mmol/L,M(Q1,Q3)] | 尿素[mmol/L,M(Q1,Q3)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 存活组 | 1.03(0.57,2.06) | 36.30(28.60,53.00) | 48.60(37.00,71.15) | 326.60(262.80,510.55) | 23.60(20.00,29.50) | 3.22(2.24,4.58) |

| 死亡组 | 2.62(0.84,9.16) | 46.50(32.50,96.70) | 96.00(52.10,250.30) | 522.30(368.20,1 354.30) | 28.00(22.80,60.50) | 3.80(3.13,5.70) |

| χ2/Z值 | 6 322.00 | 7 262.00 | 5 551.00 | 5 791.00 | 7 521.00 | 7 827.00 |

| P值 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.011 |

| 组别 | 乳酸[mmol/L,M(Q1,Q3)] | 血糖[mmol/L,M(Q1,Q3)] | P/F[M(Q1,Q3)] | S/F[M(Q1,Q3)] | 先天性心脏病[例(%)] | 其他基础疾病[例(%)] | 氧饱和度<0.90[例(%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 存活组 | 1.30(0.90,2.10) | 7.90(6.50,9.60) | 150.85(125.00,199.62) | 188.10(163.33,215.12) | 168(40.9) | 30(7.3) | 406(98.8) |

| 死亡组 | 1.90(1.20,11.40) | 9.40(7.30,15.40) | 124.80(90.33,160.22) | 160.00(129.17,189.60) | 13(26.5) | 2(4.1) | 49(100) |

| χ2/Z值 | 6 446.50 | 7 467.00 | 12 851.00 | 13 447.00 | 3.20 | ||

| P值 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.074 | 0.559a | 1.000a |

| 组别 | 菌血症[例(%)] | 多叶浸润[例(%)] | 复杂性肺炎[例(%)] | 急性肝衰竭[例(%)] | 急性肾损伤[例(%)] | ARDS[例(%)] | 低血压[例(%)] | 需机械辅助通气[例(%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 存活组 | 14(3.4) | 109(26.5) | 45(10.9) | 1(0.2) | 10(2.4) | 31(7.5) | 96(23.4) | 371(90.3) |

| 死亡组 | 6(12.2) | 25(51.0) | 13(26.5) | 2(4.1) | 12(24.5) | 14(28.6) | 27(55.1) | 49(100) |

| χ2/Z值 | 11.57 | 8.28 | 20.93 | |||||

| P值 | 0.013a | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.031a | <0.001a | <0.001a | <0.001 | 0.014a |

| 组别 | 入住重症医学科方式[例(%)] | 入重症医学科前用氧方式[例(%)] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 普通科室转入 | 门诊入院 | 120转入 | 未用氧 | 鼻导管吸氧 | 面罩给氧 | 无创辅助通气 | 气囊加压给氧 | 有创辅助通气 | |

| 存活组 | 191(46.5) | 89(21.7) | 131(31.9) | 4(1.0) | 121(29.4) | 71(17.3) | 57(13.9) | 148(36.0) | 10(2.4) |

| 死亡组 | 24(49.0) | 11(22.4) | 14(28.6) | 0(0) | 8(16.3) | 9(18.4) | 12(24.5) | 20(40.8) | 0(0) |

| χ2/Z值 | 0.22 | ||||||||

| P值 | 0.894 | 0.195a | |||||||

注:ALT:丙氨酸转氨酶;AST:天冬氨酸转氨酶;LDH:乳酸脱氢酶;P/F:动脉氧分压与吸入气体中氧体积分数的比值;S/F:脉搏氧饱和度与吸入气体中氧体积分数的比值;ARDS:急性呼吸窘迫综合征;aFisher′s确切概率法 ALT:alanine aminotransferase;AST:aspartate aminotransferase;LDH:lactate dehydrogenase;P/F:arterial partial pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen;S/F:pulse oxygen saturation/fraction of inspired oxygen;ARDS:acute respiratory distress syndrome;aFisher′s exact probability method

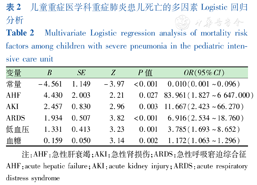

对临床资料进行单因素Logistic回归分析,将P<0.05的变量纳入多因素Logistic回归分析,结果显示血糖升高、发生低血压、AKI、AHF、ARDS是PICU重症肺炎患儿发生死亡的独立危险因素(均P<0.05),见表2。

儿童重症医学科重症肺炎患儿死亡的多因素Logistic回归分析

Multivariate Logistic regression analysis of mortality risk factors among children with severe pneumonia in the pediatric intensive care unit

儿童重症医学科重症肺炎患儿死亡的多因素Logistic回归分析

Multivariate Logistic regression analysis of mortality risk factors among children with severe pneumonia in the pediatric intensive care unit

| 变量 | B | SE | Z | P值 | OR(95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 常量 | -4.561 | 1.149 | -3.97 | <0.001 | 0.010(0.001~0.096) |

| AHF | 4.430 | 2.003 | 2.21 | 0.027 | 83.961(1.827~6 647.000) |

| AKI | 2.457 | 0.830 | 2.96 | 0.003 | 11.667(2.423~66.270) |

| ARDS | 1.934 | 0.507 | 3.82 | <0.001 | 6.916(2.534~18.760) |

| 低血压 | 1.331 | 0.413 | 3.23 | 0.001 | 3.785(1.693~8.652) |

| 血糖 | 0.159 | 0.050 | 3.14 | 0.002 | 1.172(1.063~1.296) |

注:AHF:急性肝衰竭;AKI:急性肾损伤;ARDS:急性呼吸窘迫综合征 AHF:acute hepatic failure;AKI:acute kidney injury;ARDS:acute respiratory distress syndrome

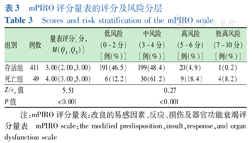

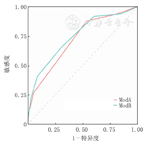

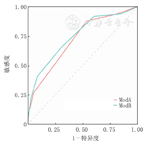

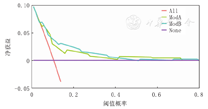

患儿mPIRO评分量表中位评分3分,死亡组评分高于存活组(P<0.001),随风险分层的增加死亡率随之增加(rs=0.27,P<0.001),见表3。mPIRO评分量表的曲线下面积(area under curve,AUC)为0.718(95%CI:0.645~0.792),最佳截断值为3分,敏感度87.8%,特异度46.5%,表明mPIRO评分量表在PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡预测具有中等区分度,见图1。

mPIRO评分量表的评分及风险分层

Scores and risk stratification of the mPIRO scale

mPIRO评分量表的评分及风险分层

Scores and risk stratification of the mPIRO scale

| 组别 | 例数 | 量表评分[分,M(Q1,Q3)] | 低风险(0~2分)[例(%)] | 中风险(3~4分)[例(%)] | 高风险(5~6分)[例(%)] | 极高风险(7~10分)[例(%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 存活组 | 411 | 3.00(2.00,3.00) | 191(46.5) | 199(48.4) | 20(4.9) | 1(0.2) |

| 死亡组 | 49 | 4.00(3.00,5.00) | 6(12.2) | 30(61.2) | 9(18.4) | 4(8.2) |

| Z/rs值 | 5.51 | 0.27 | ||||

| P值 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

注:mPIRO评分量表:改良的易感因素、反应、损伤及器官功能衰竭评分量表 mPIRO scale:the modified predisposition,insult,response,and organ dysfunction scale

注:mPIRO评分量表:改良的易感因素、反应、损伤及器官功能衰竭评分量表;ROC曲线:受试者工作特征曲线;ModA:mPIRO评分量表;ModB:改进后的评分量表;Delong检验Z=-1.97,P<0.05 mPIRO scale:the modified predisposition,insult,response,and organ dysfunction scale;ROC:receiver operating characteristic curve;ModA:the mPIRO scale;ModB:the modified scale;Delong test Z=-1.97,P<0.05

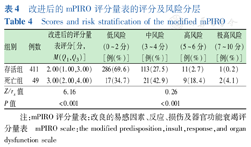

将SpO2改进为S/F评估患儿体内氧合情况,将其Q1作为截断值,即S/F≤160评为1分,应用改进的评分量表进行评分发现,中位评分2分,死亡组评分高于存活组(P<0.001),随风险分层的增加死亡率随之增加(rs=0.26,P<0.001),见表4。改进后的mPIRO评分量表AUC为0.747(95%CI:0.672~0.821),最佳截断值为3分,敏感度69.3%,特异度65.3%,表明改进后的评分量表对PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡预测具有中等区分度,见图1。

改进后的mPIRO评分量表的评分及风险分层

Scores and risk stratification of the modified mPIRO

改进后的mPIRO评分量表的评分及风险分层

Scores and risk stratification of the modified mPIRO

| 组别 | 例数 | 改进后的评分量表评分[分,M(Q1,Q3)] | 低风险(0~2分)[例(%)] | 中风险(3~4分)[例(%)] | 高风险(5~6分)[例(%)] | 极高风险(7~10分)[例(%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 存活组 | 411 | 2.00(1.00,3.00) | 286(69.6) | 113(27.5) | 11(2.7) | 1(0.2) |

| 死亡组 | 49 | 3.00(2.00,4.00) | 17(34.7) | 21(42.9) | 9(18.4) | 2(4.1) |

| Z/rs值 | 6.16 | 0.26 | ||||

| P值 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

注:mPIRO评分量表:改良的易感因素、反应、损伤及器官功能衰竭评分量表 mPIRO scale:the modified predisposition,insult,response,and organ dysfunction scale

改进后的评分量表区分度优于mPIRO评分量表(Delong检验:Z=-1.97,P=0.049)(图1),结果表明,连续NRI为0.522(95%CI:0.231~0.814,P<0.001),IDI为0.023(95%CI:0.009~0.037,P<0.05),改进后的mPIRO评分量表在预测PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡或存活的正确分类比例提高52.2%(P<0.001)。

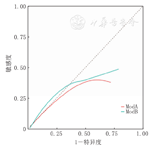

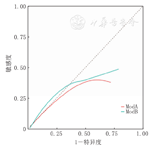

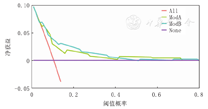

Hosmer-Lemeshow拟合优度检验示mPIRO评分量表χ2=4.94,P=0.176,改进后的评分量表χ2=1.82,P=0.611,校准曲线比较显示改进后的评分量表校准曲线总体上更靠近理想曲线,改进后的评分量表预测结果与实际观察到的结果更一致,见图2、图3。

注:mPIRO评分量表:改良的易感因素、反应、损伤及器官功能衰竭评分量表;虚线为校准度曲线,对角线为理想曲线 mPIRO scale:the modified predisposition,insult,response,and organ dysfunction scale;the dashed line is the calibration curve,and the diagonal line is the ideal curve

注:mPIRO评分量表:改良的易感因素、反应、损伤及器官功能衰竭评分量表;ModA:mPIRO评分量表;ModB:改进后的评分量表;对角虚线为理想曲线 mPIRO scale:the modified predisposition,insult,response,and organ dysfunction scale;ModA:the mPIRO scale;ModB:the modified scale;the diagonal dashed line is the ideal curve

通过DCA分析2个评分量表的临床应用价值并进行比较,结果显示当概率阈值为0.1~0.4时,改进后的评分量表的净获益高于mPIRO评分量表,见图4、图5。

注:mPIRO评分量表:改良的易感因素、反应、损伤及器官功能衰竭评分量表;DCA:决策曲线分析;All:对所有患儿进行干预治疗的DCA;None:对患儿均不进行干预治疗的DCA mPIRO scale:the modified predisposition,insult,response,and organ dysfunction scale;DCA:decision curve analysis;All represents the DCA of intervention treatment for all children;None means the DCA without intervention in all children

注:mPIRO评分量表:改良的易感因素、反应、损伤及器官功能衰竭评分量表;DCA:决策曲线分析;All:对所有患儿进行干预治疗的DCA;ModA:mPIRO评分量表;ModB:改进后的评分量表;None:对患儿均不进行干预治疗的DCA mPIRO scale:the modified predisposition,insult,response,and organ dysfunction scale;DCA:decision curve analysis;All refers to DCA,which intervenes in all children;ModA:the DCA of the mPIRO scale;ModB:the DCA of the modified scale;None means DCA without intervention in all children

既往研究显示,重症肺炎患儿占PICU住院患儿的6.7%,病死率为8.3%~13.5%,在资源匮乏的国家中占10%~80%[5,27,28,29,30,31]。近期有文献报道我国几家医院PICU重症肺炎患儿病死率为9.3%~12.4%[18,32],本研究中PICU重症肺炎患儿病死率为10.65%,与既往研究相差不大,但实际上病死率可能被低估,部分患儿因病情严重无法挽回生命,且PICU医疗费用较高,家属选择放弃治疗,这部分患儿不被纳入本研究中。

PICU重症肺炎患儿往往有严重和复杂的基础疾病或并发症,因此其死亡危险因素也复杂多样,可能与普通病房CAP或重症肺炎患儿的死亡危险因素有所区别。既往研究显示,在CAP患儿中年龄、性别、基础疾病和早产等与死亡相关,为死亡的独立危险因素,多见于发展中及资源匮乏的国家或地区[4,18,33]。但本研究及近期相关研究均显示[18,32],年龄、性别、基础疾病及早产与PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡不相关,可能原因为社会经济水平及医疗条件有所不同,同时入住PICU的重症肺炎患儿大多年龄较小,合并先天性心脏病、营养不良及早产等,因此其在PICU重症肺炎患儿的死亡评估方面不具有特异性。有研究报道在PICU或急诊科的重度CAP患儿中,常见死亡原因为多器官功能衰竭、心血管功能障碍,早期死亡多见于心血管功能障碍,晚期死亡多见于多脏器功能衰竭[34]。本研究Logistic回归分析发现,发生低血压、ARDS、AHF、AKI和血糖升高是PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡的独立危险因素,与既往CAP患儿死亡风险因素的研究相一致[4,8,9,10,12]。既往多项研究报道,菌血症为肺炎患儿死亡的独立危险因素[5,35,36],本研究中菌血症与死亡相关,但不为PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡的独立危险因素,可能原因为血培养阳性率较低,患儿入住PICU前已于外院或普通科室使用抗生素治疗,导致血培养假阴性,影响研究结果。

mPIRO评分量表是基于国外28 d至15岁CAP患儿临床特征构建的,在儿童CAP死亡预测及风险分层方面具有高度区分度,田颖[37]首次将其应用于国内重症CAP患儿的死亡预测,研究显示其区分度远小于国外该量表的表现,本研究中mPIRO评分量表对PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡预测具有中等区分度,区分度进一步下降,推测可能由于人群变化、疾病的危险因素、未测量的危险因素、治疗措施及治疗背景随时间变化,模型会发生校准度漂移。同时mPIRO评分量表所选择的变量虽与CAP患儿死亡显著相关,但均为主观选择且各指标均评为1分,未进行变量筛选及模型拟合[4],可能使其在使用或外部验证时稳定性和区分度不佳。

低氧血症是因肺炎住院儿童死亡的强预测因子[38]。P/F、S/F排除了FiO2对PaO2、SpO2的影响,其水平越低患儿病情越重,死亡风险越高[39]。成人PIRO评分量表中应用P/F评估ICU重症肺炎患者的氧合情况[40]。S/F具有无创、方便和实用的优点,为P/F的替代指标。因此,本研究采用S/F对mPIRO评分量表进行改进,改进后的评分量表在区分度、校准度及临床应用价值方面均优于mPIRO评分量表,表明S/F更能准确识别出PICU中严重低氧血症的重症肺炎患儿,并指导治疗。但改进后的评分量表敏感度明显下降,且敏感度和特异度均较低,结合上述mPIRO评分量表本身的缺点,因此需要基于我国PICU重症肺炎患儿的临床特征重新构建模型。

综上,本研究分析了PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡的危险因素,验证了mPIRO评分量表在PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡预测方面的临床价值,同时对其适当改进,为PICU重症肺炎患儿死亡风险评估方面提供了新方法。本研究为回顾性单中心研究,未来需多中心、大样本临床研究进一步验证。

所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突