乳糜泻是一种易感人群摄入麦麸物质后引起由免疫介导的慢性小肠吸收不良综合征。目前北美及欧洲发病率为1%~3%,该病既往被认为在我国十分罕见,但现在多项研究已证实中国慢性腹泻患儿中存在该病。儿童罹患乳糜泻可导致生长发育受限及多种并发症,而通过去麸质饮食后症状即可明显改善。因此,早期诊断和及时治疗对提高患儿生活质量意义重大。

版权归中华医学会所有。

未经授权,不得转载、摘编本刊文章,不得使用本刊的版式设计。

除非特别声明,本刊刊出的所有文章不代表中华医学会和本刊编委会的观点。

乳糜泻(Celiac disease,CD)是一种由于遗传易感个体摄入麦麸物质导致的慢性小肠吸收不良综合征。最早在1888年由Samuel Gee首次报道,直至1953年研究人员才明确该病与麸质有关[1],因此,又称为麸质敏感性肠病。目前其在北美及欧洲发病率为1%~3%[2,3,4]。作者之前的研究证实,在中国慢性腹泻的患儿中确有CD的存在[5],同时国内也有成人患CD的病例报道[6,7,8]。近年来随着研究的深入,人们对其发病机制、易感基因有了进一步的认识,且随着血清学、基因检测等检查手段的发展,人们发现实际的患病人数可能远高于目前临床诊断的人数。因此,学习及掌握其有效的诊治手段、提高对疾病的认识和诊治水平是亟待解决的问题。

CD临床表现多样,典型症状为消化道表现,主要有不明原因的慢性或间歇性腹泻、脂肪泻、腹痛、腹胀等;同时患者还多伴因小肠吸收障碍导致贫血、体质量减轻、生长发育迟缓等问题;幼儿可表现为嗜睡、易激惹等精神症状,青少年可表现为矮小、缺铁性贫血、青春期闭经等症状;部分患者可出现疱疹样皮炎、代谢性骨病、牙釉质缺损、肝功能异常、周围神经病、共济失调及癫痫等神经性疾病等异常[9,10]。不同年龄的人群其临床表现不尽相同,婴幼儿最早6个月就可出现症状[11]。最近研究显示,相当多的患儿可无消化道症状,仅表现为肠外症状,如贫血、生长不良、缺铁、肝酶升高等,这些也可以是CD患者的唯一症状。还有部分患者可能是无明显症状的隐性患者,往往通过筛查被发现[12,13]。

1型糖尿病、自身免疫性甲状腺炎、唐氏综合征、Turner综合征、Williams综合征、选择性IgA缺陷等患者及CD的一级亲属,是CD的高发人群[9]。针对既往流行病学研究显示,CD一级亲属患病比例为1︰13,二级亲属患病比例为1︰15[14],有消化道症状及相关疾病人群中CD的患病比例为1︰56,而普通人群CD的患病比例为1︰133[15]。Whitacker等[16]研究显示,1型糖尿病的儿童中CD的发生率约为4%,较健康人群高。

遗传因素在CD的发病中起重要作用[17]。HLA Ⅱ类分子中DQ区域,特别是HLA-DQ2(DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201)及HLA-DQ8(DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302)的表达被认为与CD的发病有关[18-19],既往研究认为,CD患者约90%携带HLA-DQ2基因,而5%携带HLA-DQ8基因[20]。过去认为中国人群很少携带这些基因,因此患CD的可能性也很小。但最近研究显示,中国江苏人群中含HLA-DQ2的比例为7.2%,含HLA-DQ8的比例为4.7%[21]。然而并不是所有基因携带者均会发病,在30%~40%携带此基因的人群中仅有1%的人会发病[18,22]。其他一些基因表达也与CD有关,如CTLA-4[23]、MYO9B[24]等,但其是否在不同人群中均有意义还有待进一步的研究证实。因此,基因检测阳性不是CD诊断的必须依据,目前仅用于CD高危人群的筛查及协助疑似CD患者明确诊断。

血清学检查是筛查和诊断CD的重要手段,由于其操作简单易行,且成本较低,越来越被人们所推广。目前主要的检测内容有抗肌内膜抗体(endomysiumantibo-dies,EMA)、抗组织转谷氨酰胺酶抗体(anti-tissue transglutaminaseantibodies,anti-TTG)、抗脱酰氨基麦胶蛋白肽(anti-deamidatedgliadin peptide antibodies,anti-DGP)及抗麦胶蛋白抗体(anti-gliadin antibodies,AGA)。AGA早在20世纪80年代初就已被发现,针对2岁以上患者的研究显示,AGA IgA及IgG的敏感性及特异性分别为88%~100%及71%~97%,因此,在过去几十年中AGA曾较多应用于CD患儿的筛查及诊断[25,26,27]。但随着自身抗体如EMA及TTG等麸质特异性抗体的发现,AGA已逐步被取代[28]。EMA是CD患者在胃肠道平滑肌内膜产生的特异性抗体,研究证实这些抗体多由IgA组成,其敏感度及特异性均高于AGA,故目前广泛应用,EMA的结果目前更被用来作为检测其他抗体特异性的参考标准[9,29,30]。TTG在体内具有多种作用,其可与麸质蛋白结合,参与诱导肠黏膜表面T淋巴细胞活化,CD患者体内多有其特异性抗体。在最新的针对儿童研究中TTG特异性为99.5%,敏感性为96.0%[31,32]。EMA及TTG是目前公认的敏感性及特异性均较高的检查方法,在欧洲小儿胃肠营养学会(ESPGHAN)及美国胃肠病学会(ACG)最新针对CD的指南中它们是诊断CD的重要依据[9,33,34,35]。DGP对于CD的检测同样具有较高的特异性,为90%~98%,但敏感性在部分研究中相对偏低[10,25]。对于上述抗体阴性但高度怀疑CD的患者可行DGP。近期有研究提出,对于小年龄儿童(<2岁)IgG DGP更具有参考意义[36,37]。此外,需注意对于IgA缺乏(总IgA<0.05 g/L)的患儿需行相关的IgG抗体才能检出疾病[33,38]。

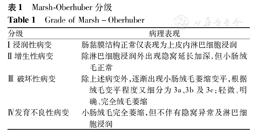

尽管CD的病理改变是非特异性的,但病理学仍是CD确诊的金标准。过去仅有典型小肠绒毛改变的患者才被诊断为CD,近年人们对CD组织病理学变化的认识有所改变,Mulder等[39,40]研究认为CD小肠绒毛的改变是一个进行性的过程并可表现为多种形式,并建立了相关的分级标准,目前多应用Marsh-Oberhuber分级(表1)。越来越多的临床研究表明,虽然Ⅲ期病理改变是CD的典型病理改变,但CD患者小肠绒毛也可出现Ⅰ、Ⅱ期的病理改变,甚至有研究显示血清抗体阳性但组织学正常的患者也可能为潜伏和隐藏的CD患者[41]。因此,目前指南提出对于疑似CD患儿血清学检查阳性同时病理表现符合Marsh Ⅱ~Ⅲ级可明确诊断,若病理正常或符合Marsh Ⅰ级表现建议进一步完善其他检测;针对CD患儿的病理活检建议十二指肠球部留取1、2块病理组织,十二指肠远端应不少于4块病理组织[9]。

Marsh-Oberhuber分级

Grade of Marsh-Oberhuber

Marsh-Oberhuber分级

Grade of Marsh-Oberhuber

| 分级 | 病理表现 |

|---|---|

| Ⅰ浸润性病变 | 肠黏膜结构正常仅表现为上皮内淋巴细胞浸润 |

| Ⅱ增生性病变 | 除淋巴细胞浸润外出现隐窝延长加深,但小肠绒毛正常 |

| Ⅲ破坏性病变 | 除上述病变外,逐渐出现小肠绒毛萎缩变平,根据绒毛变平程度又细分为3a、3b及3c:轻微、明确、完全绒毛萎缩 |

| Ⅳ发育不良性病变 | 小肠绒毛完全萎缩,但不伴有隐窝异常及淋巴细胞浸润 |

1969年北美儿科胃肠病、肝脏病及ESPGHAN制定了第1个CD诊断指南,其中将与麸质因素相关的临床症状及小肠活检具有典型病例改变作为CD的诊断标准[42]。随着血清学检测技术的不断提高及人们对于CD的深入研究,2012年ESPGHAN对CD制定了新的诊断指南:(1)对于临床表现疑似CD患儿,首先进行TTG等相关血清学检测(IgA缺乏者行IgG或IgM检测),阳性者可行十二指肠黏膜活检,合并有小肠黏膜损伤(Marsh Ⅰ~Ⅲ级)的患儿可诊断CD,建议去麸质饮食(gluten-free diet,GFD)。(2)对于血清学阳性而无黏膜改变的患儿则可复查病理或行其他血清学和基因学检测以明确诊断。(3)对于无症状高危儿童可行基因学检测,若阴性则CD发生可能性极低,若阳性需完善血清学检测(>2岁后)以明确诊断。此外在2012最新指南中提出若患儿满足以下4项则可考虑诊断为CD,无需小肠病理活检:(1)具有慢性腹泻、生长发育迟缓肠道内外症状、体征提示CD;(2)anti-TTG血清学检测(IgA缺乏者行TTG-IgG检测)超过正常值上限10倍;(3)EMA血清学阳性;(4)HLA-DQ2或DQ8基因阳性[9]。但目前对于儿童确诊是否需行小肠活检仍存在争议,在2013年ACG的最新指南中建议病理活检为明确诊断条件,并指出针对2岁以下儿童DGP与TTG结果结合更具有参考意义[35]。

CD一旦确诊,患者就需要坚持终生的GFD,GFD是目前唯一有效的治疗方案,尚无有效药物方案。GFD需要严格避免所有的含麸质蛋白质(即面筋)产品、避免小麦、大麦和黑麦,但现实中这是不可能的,故目前定义其为饮食中所含麸质蛋白水平极低不会导致病变。虽然研究显示大部分患者能够耐受的麸质含量为34~36 mg/d,但其中仍有患者出现肠黏膜的改变,因此,目前认为<10 mg/d的麸质饮食较为安全[43]。有研究显示通过16个月的GFD饮食,尽管有83%的CD患者血清学检测转阴,但仅有8%的患者组织学恢复正常,提示GFD的疗效并没有人们想象的那么迅速,但研究还是证实了严格的GFD饮食可明显降低临床症状及并发症的发生[44]。对于儿童CD患者指南中建议以每6~12个月复查血清学指标作为评估GFD的指标,直至降至正常。欧美国家有专为CD患者提够的GFD食物,但如何保证长期完全无麸质的饮食并补充生长所需的营养物质,需要患者、家长及临床或营养医师等共同的努力。由于GFD食物昂贵,且并非所有国家均已提供、商品食物中添加成分可能还有麸质物质患儿饮食控制困难等问题,一些学者希望通过抑制免疫反应来控制CD的病程,如Silano等[45]从硬质小麦中提炼出一种可溶于乙醇的10肽,其可以作为麸质蛋白的拮抗剂,抑制CD的免疫反应。但目前只有2种药物进入Ⅱ期临床试验阶段:一种为ALV003(一种口服重组特异性麸质蛋白酶),其可减少由麸质导致的肠黏膜损伤[46];另一种为Larazotide(一种口服肽类),其调节肠上皮紧密连接,减轻患者的症状[47]。同时研究显示CD患者体内微量营养素、维生素(铁、叶酸、维生素D、维生素B12等)多不足,故对于新诊断的CD患儿均建议其及早完善维生素及微量元素检测并及时补充,有利于预防并发症的发生[48,49]。

CD在中国的发病情况已受到越来越多学者的关注,了解这一疾病,发现并诊治该病,无论对患者还是临床研究者都有重要意义。而如何经济、有效并及时诊断CD,发现潜在的患者也是研究者正在努力的方向。在治疗方面,有研究者正设法运用生物技术抑制CD的免疫反应,使CD患者能正常饮食,如果这些研究能成功并运用于临床,对于CD患者无疑是最好的消息。